Translated into English by Aimee Van Vliet.

The valley unfurled beneath him, squeezed between two high walls of rock as if the mountain had been cut into, leaving a jagged wound. Trees growing on the terrain clung to the rock, their stubborn roots grasping at a precarious balance. But as he looked through the viewfinder, all he saw of it was the winding road that curved along its bottom, running along the left side of the river. With one hand on the trigger and the other holding the barrel of his rifle, he aimed right at the centre, right there, where the German vehicles and soldiers were moving. He shot without pausing, one magazine after another, six shots at a time.

In the deafening fury of the battle around him, my grandpa was almost shocked at the clarity with which he observed the scene. Every blade of grass rippling before him, every speck of dirt that he moved with his elbows, every movement of the men at the bottom of the valley appeared in sharp focus. In the midst of his first battle, his mind wandered high above, alighting here and there on a detail, occupying a distant, sterile place, out of time.

He hadn’t yet realised it, but he had lost all awareness of his body. His legs, which lay splayed out behind him on the ground, were shaking as if they were about to break. The shoulder on which he rested his rifle was blasted by the recoil each time he pulled the trigger. His head, squeezed into his helmet, bounced with every shot. And his jaw was clenched so tightly his teeth might have crumbled, while a low, constant moan emanated from his mouth, the sound of a wounded animal.

Luckily, he felt none of this. Adrenaline had been merciful enough to take over for him, taking his hand and guiding him to a safe place far away, from where he could observe everything without fear or hurry. The sliver of awareness that still clutched to reality registered the absurdity of the situation with a sense of shock. That morning he had woken up, got dressed, met with his men and eaten with them. They joked to relieve some tension, lit cigarettes and eventually started on their way. It seemed like any other day, the same as so many others that had gone before. It was warm, the late summer sky was a dazzling blue, and a sea breeze wafted in from the coast. That day, however, they would walk, under their own volition, towards their baptism of fire. That sequence of unremarkable daily actions that had led him, step by step, towards his first mortal combat with the German army seemed so incoherent as to be inexplicable, as if no logical sequence could have led to that conclusion. There was a gaping chasm between everything he had done before the moment of firing his first shot, and what he was living through now, an abyss which, once crossed, would leave him gripping on to chaos and madness for dear life. How could he have ended up there?

The answer to that question lies three months earlier.

In June of 1943, after Axis forces had been pushed out of North Africa once and for all, the Nazis began to fear Allied landings at various points around the Mediterranean. In order to reinforce the defences prepared by the Italians, and perhaps even to keep an eye on their movements following recent military defeats, they shifted the SS Reichsführer mechanic brigade to Corsica, with the order to govern the southern part of the island.

The Germans’ arrival on the island created tension and confusion, although to begin with they coexisted peacefully with Italian troops.

The following month, however, events began to spiral.

On the 9th July, the Americans launched Operation Husky, landing in Sicily. The invasion took Axis forces by surprise, as they were expecting the Allied attacks to occur in Greece and Sardinia and had left southern Italy without reinforcements. The confusion among Italian and German military leaders was also the result of an elaborate espionage operation, in which fake British documents were brought to the Nazis in order to convince them that any landings in Sicily would be a mere diversion.

Hitler himself fell into the trap. On the 14th May he had met with Admiral Donitz to discuss developments in the war. In his notes, the Admiral wrote that the Führer “did not agree with Mussolini that the most likely point of invasion would be Sicily. Furthermore, he believes that the discovered British-American order confirms the hypothesis that any planned attacks will be on Sardinia and the Peleponnese”. For once, Hitler would have been better off listening to Mussolini.

When the Allies began to flood into Sicily, the entire edifice of the fascist regime, which had been teetering for some time, began to collapse. For some Italians, the arrival of the British and Americans was the sign that a new period was beginning. For others it was simply the straw that broke the camel’s back.

A few days after the landing, on the 19th July, Hitler, concerned by Mussolini’s apparent apathy, met with Il Duce personally in San Fermo di Belluno, at Villa Gaggia, and informed him that according to German intelligence the King of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele III, was plotting to have him replaced by Pietro Badoglio. Mussolini appeared worn out in that period and during the meeting was capable of nothing more than an inscrutable silence. The Führer had hoped to obtain permission for his army to enter Italy. The meeting ended quickly, however, before any decisions could be reached, due to the first heavy Allied bombing of Rome, which was unleashed at the very same moment. When Mussolini rushed back to the capital, piloting his personal aircraft, he could see the eastern neighbourhoods of Rome still in flames.

On the afternoon of the 24th July, the Grand Council of Fascism, the highest ruling body of the National Fascist Party from 1922, met in the Parrot Room in Palazzo Venezia in Rome, to discuss the dramatic direction the country’s situation was taking.

Mussolini opened the session by admitting that the war was in an “extremely critical” phase. He complained that coastal divisions had buckled just three hours after the Allied landing in Sicily. He complained too about the Sicilians, who “welcomed the British and Americans as saviours”. He did not seem interested in shouldering any blame – mistakes were always someone else’s fault. Finally he turned to those present and asked what the Grand Council’s intention was: to continue the war or capitulate? It was clearly a rhetorical question. At the end of his speech, he even said: “I want to make it very clear that Britain is not waging war against fascism, but against Italy. The British want a century before them, to keep their bellies full. They want to occupy Italy and keep it occupied. And then, we are committed to the pacts. Pacta sunt servanda”. In conclusion: he wanted nothing to do with the idea of splitting from Hitler.

After Mussolini, it was the turn of Dino Grandi, President of Parliament and former Minister of Justice. During his speech he proposed a motion (‘Ordine del Giorno’), of which the aim was to end the fascist experiment once and for all. He had discussed it the previous day with Galeazzo Ciano and divided it into three sections. The preamble was a long rhetorical passage, appealing to the Nation and the Armed Forces, praising them for resisting the invaders. The second part called for the restoration of pre-fascist institutions and laws. The conclusion was an appeal to the King, whom they asked to take on supreme civil and war powers, under Article 5 of the Albertine Statutes, or the Constitution of the Kingdom.

Following Grandi’s speech, Ciano, as if reading from a script, took the floor to defend the motion. Mussolini listened, making no attempts to conceal his impatience. Defiant, Ciano closed his address by accusing Germany of starting a war that no one really wanted or had planned. On the subject of a possible split with Berlin, he said “Pacta sunt servanda? Of course: but only when the other side shows basic loyalty. We Italians have always observed the pacts while the Germans never have. Our loyalty was never reciprocated. Whatever happens, we shall never be traitors, rather we shall be betrayed”. These words contributed to him being sentenced to death and executed a little under six months later.

Several successive speeches prolonged the meeting. After 11pm the session was suspended for half an hour. On resuming, Mussolini attempted a final manoeuvre, declaring that “anyone calling for the end of the dictatorship wishes the end of fascism”. He now seemed almost uninterested in the entire thing. Indeed, he did nothing to prevent a vote on Grandi’s motion.

Voting took place at 2:30am. With 19 votes in favour out of 28, including those of Ciano and Bastiniani, who had helped to save the Jewish community in the French territories occupied by Italy, the motion was passed. “Sirs” said Mussolini, “you have unleashed a crisis in the regime”. His wife Rachele, when he returned home, asked whether he had had the insurgents arrested. “I’ll do it tomorrow” he said. “Tomorrow will be too late”, she answered with a sigh. She understood what would happen. A simple cabinet reshuffle, as perhaps Il Duce imagined, would not be enough to divert the crisis.

Indeed, the next day he met with Vittorio Emanuele III at Villa Savoia, today Villa Ada, who informed him that he had handed the government to Badoglio. “So it is all over” exclaimed Mussolini, crumbling. With the pretext of wishing to protect him, the King had him escorted out by the carabinieri, who put him under arrest and took him away in a military ambulance. The plan of capture had been developed by General Castellano with the help of General Carboni. Both would soon play a role in signing the armistice with the Allies.

When news spread about the fall of fascism, the whole of Italy rushed into town squares to repudiate it in noisy, spontaneous events. Suddenly, Italians realised that they were antifascists. Of those who up until a few days earlier were singing Mussolini’s praises, Benedetto Croce said: “It is not unexpected, but it is always repugnant to see the spectacle surrounding rapid political changes”. The few rebels who were imprisoned during the twenty year fascist regime were surprised to find that they were now a minority within this new wave of antifascists. This was similar to what the partisans experienced towards the end of the war, when, sensing that danger was retreating, their ranks swelled with new arrivals, keen to clear their names and jump on the winning bandwagon.

Once he was installed in government, Badoglio went about abolishing the fascist party and the Grand Council of Fascism. When Hitler was informed about the events in Italy he completely lost control. He began to scream “Treason! Treason!” at the top of his lungs, incapable of containing his rage. One of his generals, who was present at the scene, described it as an “astounding, overwhelming display of mental confusion and imbalance”.

At that point, Italy was in the unfortunate position of being viewed with distrust both by the Nazis, who considered it a former partner on the cusp of joining the Allies, and by the British-Americans, who did not yet trust the new government. And indeed, their air raids continued; Milan and Turin were badly hit in August 1943.

My grandpa, like all Italian soldiers, followed the news from Rome anxiously in that period. Everyone was wondering what would happen, whether they would suddenly be forced to fight the Germans, or whether they would be overwhelmed by an American invasion of Corsica. Some began to dream that they would be allowed to return home immediately. Others, lost in even more outlandish fantasies, declared that fascism was not dead, and neither was the alliance with Germany.

In the chaos of conflicting news, rumours began to spread like wildfire among the Italian troops. My grandpa tried to reassure his men as best he could, but the reality was that he had little to offer them. He went among the men, trying to hide his nerves, to avoid spreading panic. Only two people were close enough for him to share his deepest thoughts: a former schoolmate from Pola, second lieutenant Enrico Mazzoni, and his orderly, bersagliere Mario Borghi.

Enrico Mazzoni came from Novi Ligure and, like my grandpa, was born in 1921. They met at the Pola officers’ school, passing out on the same day, and both were assigned to the XXXIII battalion of cyclist bersaglieri, 9th company. Mazzoni was an intellectual, but his sensitive soul was trapped in a fearless body. Over the course of the war he would distinguish himself in battle, starting from Corsica. After the war, he devoted himself successfully to developing the cultural life of his town, first becoming the headmaster of his local Scientific Secondary School, then co-founder and teacher at the Novi Ligure Senior Citizens’ University, and lastly president of the ‘In Novitate’ Centre for Studies, which still today organises historical, cultural, religious and sporting activities in Novi.

Mario Borghi, also born in 1921, was less fortunate – his life took quite a different turn. My grandpa’s memory of him was clear, though. When he spoke about him to me as a child, his eyes lit up with excitement, before his voice faltered and he had to look away. Time changes the weight of memories: some become lighter and fly away, others become lodged somewhere and start to sink like heavy rocks.

They met when Borghi was assigned to his unit in Tuscany and saluted as he introduced himself as his orderly, a military role that no longer exists but that at the time was used to describe a solider that was responsible for personal assistance to an officer. Over the long months that they spent together, Borghi became much more for my grandpa than a subordinate at whom he could shout orders. They found themselves contemplating death at each other’s side, leading to an almost transcendental connection.

The high command intervened to put a stop to the soldiers’ chatter. On the 26th July, the day after Mussolini’s arrest, General Magli issued a message to the troops in Corsica, stressing that the army had “always been loyal to the King and removed from politics”. It was not yet a clear indication of the road to take, but it was a step that distanced him from Mussolini and his association with Hitler.

My grandpa, who grew up with an honourable sense of authority and duty that today would border on the ridiculous, was heartened. For him, the King had always been the most important point of reference, embodying the ultimate unity of the country, a sort of inviolable bulwark holding out against political turbulence.

His views on this point would change over the course of his life, but in the immediate postwar period, and unlike his future wife Ginetta, he voted to preserve the monarchy at the 1946 referendum.

Having received Magli’s communication, he gave his men an encouraging smile and prepared to face those difficult days in which everything seemed to hang by a thread.

Meanwhile Badoglio, realising the impossibility of continuing the war, had decided to begin negotiations with the Allies. Exactly what the Germans feared he would do.

Having delivered Mussolini to the safety of the Campo Imperatore hotel at Gran Sasso, or so he thought, he gave instructions to General Castellano to find the Americans and sign an armistice. The only condition requested by Castellano was that the Allies intervene directly on the Italian peninsula, to which they agreed. However, in order to speed up negotiations, Eisenhower threatened a massive bombing of Rome, which was called off at the last minute when the official document was finally signed on the 3rd September in Cassibile, province of Siracusa. The American signatory was the future director of the CIA, Walter Bedell Smith.

In the days immediately following the signature, the armistice was kept a secret. Badoglio wanted to give the army time to ready their defence of Rome against the Germans, who had already flooded Italy with 8 divisions and one Alpine brigade, taking control of Liguria, the mouth of the Tiber, Alto Adige and Emilia Romagna. As was to be expected, the Germans were not caught unawares by the fall of fascism: the plan to occupy Italy militarily, and neutralise its armed forces, known as Operation Achse, had in fact been drawn up as early as May 1943.

In anticipation of the announcement of the armistice, on the 5th September the Italian General Staff drafted what was known as “Memorandum 1”. It was essentially a strategic document, describing how the army should defend itself against possible Nazi attacks, and how to hold on to the airports not yet held by the Nazis. This was an essential precondition for the arrival of Allied paratroopers into Rome, who would act to protect it against German troops. This sort of plan would have been achievable were the defences of the capital and the airports to hold. Instead, General Carboni, who was in charge of the protection of Rome, lost his nerve. Despite having the numerical advantage, he claimed that he would not be able to hold out against the Germans for more than six hours. Badoglio, infected by his subordinate’s panic, backed him up and asked for the Allied operation in Rome to be cancelled, as well as for a delay in the announcement of the armistice. Eisenhower cancelled the air mission but refused any further postponement of the armistice, and at 6:30pm on the 8th September he made a public announcement over the radio, going ahead as if Badoglio had agreed to it.

Faced with this fait accompli and fearing Allied retaliation, the Italian command accepted the situation. Around an hour later, Badoglio too announced the armistice, and stated that “any act of aggression against British-American forces by Italian forces must cease in every location. They may, however, respond to attacks from any other source”. This was unlikely to be enough to coordinate the movements of the Italian army, which suddenly found itself cut adrift.

The Allies were already moving up through Calabria, and lost no time, landing the next day in Salerno and Taranto.

At the same time, Vittorio Emanuele III and Badoglio hurried to leave Rome and take refuge in Brindisi, along with several government, military and royal representatives. The speed with which they fled meant that the Italian army, which was still around a million men strong throughout the peninsula and in Sardinia, could receive no precise orders or move in a coordinated way. All initiative was left to the unit commanders, who often faced German ultimatums to surrender and give up their weapons. Entire Italian units stopped fighting, and the German bounty was huge. In some cases, Italian soldiers were simply annihilated, as was the case of the Acqui division in Kefalonia.

By the end of Operation Achse, the Nazis had gained 800,000 Italian prisoners and seized vast reserves of supplies and materials. General Jodl, in charge of occupying Italy, wrote in his report of the 7th November 1943 that “we have found raw materials in much higher quantities than we expected, given the Italians’ constant economic requests until now”.

While the King, in Puglia, was setting up the so-called Kingdom of the South, under the direct orders of the Allies, Mussolini was rescued by German paratroopers. On the 12th September he was liberated from Gran Sasso, in one of the last successful Nazi operations. He was transported to Germany and met with Hitler three days later. Il Duce, by this point in a precarious state of health, expressed his impossible desire to disappear from public life, to retire like anyone else. But it was too late. The Führer threatened to destroy Milan, Genoa and Turin if he did not cooperate with his plans. So it was that Mussolini reluctantly agreed to obey the orders he received and set himself up as the Head of State and Prime Minister of the Italian Socialist Republic of Salò, proclaimed on the 23rd September. Everything was in place for the civil war that would rip through Italy for almost two years.

The events of the 8th September swept up all Italian soldiers like a hurricane, including my grandpa and the units stationed with him in Corsica.

General Magli learned about the armistice at 7pm on the 8th September, not from Rome, but listening to the BBC. The information arrived in the nick of time, as a few minutes later he arrived at dinner, a prior arrangement, with the German commander in Corsica, General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin. He sat through the meal grim faced, as after the fall of fascism Magli had received pressure from his Nazi counterpart to install German artillerymen in the Italian coastal batteries. Understanding as he did that von Senger und Etterlin was attempting to exert some control over his troops, Magli refused outright. And now he found himself having to discuss Italy’s new position, of which he had been informed through pure luck just a few moments before.

After the awkward dinner, the conversation continued in the Italian general’s office. Magli clarified that from that moment onwards the Italian army would launch no further offensives against the French or the Allies. In return, the German general announced his wish to abandon Corsica with his men. Magli therefore offered him the freedom of movement required to withdraw, hoping that that would be enough to avoid further bloodshed.

But von Senger und Etterlin had simply been trying to put a good face on a bad lot. Once he had taken leave of Magli, he returned to his command centre and shortly afterwards, at half past twelve at night, German troops launched a sudden, violent offensive on the port of Bastia. The Italian guards were taken completely by surprise and the city quickly fell into Nazi hands. 27 Italian soldiers lost their lives during the attack. Some were sleeping and were stabbed to death in their quarters before they could even take part in the battle.

Magli was informed while the offensive was still raging, and reacted angrily, ordering his men to counterattack and take back the port. At dawn on the 9th September, the Italian artillery, strategically positioned at the citadel of Bastia and the surrounding fortresses, swung into action. German positions were targeted and heavily hit. Once the bombing was over, Italian forces rushed into the city, forced the port and won it back. According to some estimates, 75 Italians and 160 Germans lost their lives in this conflict.

Knowing themselves to be outfought, the German survivors attempted to reach safety by fleeing on board their vessels, leaving the port in a hurry. Magli, however, did not want to let them get away and ordered an intercept. The Italian torpedo boat Aliseo, which was cruising off Bastia, returned to the port and caught up with the departing German fleet. In just a quarter of an hour, from 8:20 to 8:35 in the morning, and in spite of the damage caused by enemy fire, it attacked and sank two German submarine chasers and five naval ferry barges (Marinefährprahm). The German losses were almost total: only 25 survivors were fished from the sea. For this action, the commander of the Aliseo, frigate captain Carlo Fecia di Cossato, was awarded the gold medal for military valour.

Without realising it, the Italian soldiers involved in these battles were part of one of the few victorious reactions to Operation Achse. The units controlling southeastern France were less lucky. They quickly crossed the Alps to return to Italy, heading towards Turin and Cuneo, where they surrendered to the Germans.

Some of the soldiers that were part of those units managed to hide and take to the mountains, where they joined the partisans. Among them was General Antonio Trabucchi, the former Chief of Staff of the 4th Army that had occupied France, who would later be given single general command for all partisan combat operations in Piedmont.

While Corsicans had already begun to celebrate the armistice and the end of Italian occupation, discharging the few hunting or military guns they still owned, news of the conflict in Bastia flashed through the Italian contingent like lightning.

“What do we do now, Sir?” Borghi asked my grandpa, a jolt of fear in his eyes. He was tight lipped, attempting to maintain a semblance of self-control. But my grandpa could hear his heavy breathing and noticed that he was holding the fabric of his trousers with white knuckles.

“Don’t worry, for now at least we have the upper hand. And Fucci will know what to do”.

Ettore Fucci was the commander of the 10th Mobile Division, of which my grandpa’s unit was a part. He had a determination that bordered on madness. He too was a bersagliere, born in 1895 in Barletta. Over his long military career, he participated in both world wars, played a key role in the war of Italian liberation, was injured four times, mutilated in both legs and was awarded four Silver Medals, two Bronze Medals, two War Crosses for military valour and five Ordinary War Crosses. This was a man that the soldiers were happy to have on their side, and whom they looked at with a mixture of admiration and fear. And to whom nobody could say no.

Having come out of his first conflict with Italian troops badly, General von Senger und Etterlin attempted another bluff. On the night of the 9th September, having lost the port of Bastia, he returned to find Magli at the Italian command centre in Corte. He appeared cap in hand and apologised for the incidents of the previous night, accusing his direct reports of not having listened to him, and promising that there would be no repeat. Magli listened to him with gritted teeth and once again guaranteed him free movement, on the condition that he withdrew from the island. He also added that he would tolerate no aggression.

Once again, events disproved the sincerity of von Senger und Etterlin’s words. And cast Corsica into an uncontrollable spiral of violence.

While the German general was conferring with the Italian commander, German reinforcements were rushing to Corsica from Sardinia, where they had been stationed. The attack on Bastia had merely been a distraction and a diversion to gain time. The men of the 90th Panzergrenadier Division landed on the 9th September in Bonifacio and on the 10th in Porto Vecchio.

Realising what was happening, the Corsican partisans asked the Italians to join forces with them. Two treaties were drafted in Bastia. The first stated that “the signal has been given. It is therefore your duty to join with the Corsican people, with their cause. Be by their side as you together sing the Marseillaise and Garibaldi’s anthem. Show your joy (…). Do not surrender your weapons, you must keep your guns or turn them in to your Corsican companions. Death to the OVRA criminals, death to murderous carabinieri. Death to the Vichy traitors. Long live freedom and the brotherhood of peoples”. The second suggested a certain admiration for the events in Bastia of the previous night: “Italians! Join with us in this hour of joy. Let the Latin blood running through our veins be the sacred link between Corsicans and Italians. We admired your defeat of the Germans last night (…) Be by our side. For peace, for freedom, for Latin brotherhood”.

Magli decided to accept the partisans’ offer. On the 10th September he met with Paulin Colonna d’Istria, the head of the resistance on the island, in Corte. An official in the French army, he had been in Africa when the Second World War had broken out. Once he joined the resistance, he was taken to land on the east coast of Corsica by a British submarine on the 4th April 1943, to direct the operations of the Front National. Magli promised his former enemy that he would return to the partisans the weapons that the Italians had confiscated from them over previous months.

The same day, Magli informed German high command that they were to use only one road to move their troops to the port of Bastia and leave the island: the road that ran along the east coast of Corsica. Magli also specified that the rest of the Corsican territory should remain under direct Italian control, including the city of Bastia. The Germans took note but did not respond. An icy veil had been drawn between the former allies.

The person who finally brought some clarity to the situation was the Italian Chief of Staff, General Roatta. The next day, at 10am, he sent Magli an explicit message: “Consider German troops the enemy”.

One hour later, Magli gathered around him his war council, and gave orders to all the large Italian units. His plan foresaw attacking the Germans at various points around the island, in particular in Bonifacio and Porto Vecchio, where they had landed, as well as forming several clusters of resistance fighters to deal with any German counterattacks. In parallel, Corsican partisans would be used to attack German warehouses and outposts.

The plans were laid, everything was ready. But the Germans were too fast.

Von Senger und Etterlin attacked first, shattering Magli’s plan. At 5pm on the 12th September, the Germans appeared suddenly at Casamozza, a village to the south of Bastia, the control of which was essential both to guarantee traffic along the river Golo, which cuts across the road to Bastia and crosses the north east of Corsica, and to access the city’s airport.

The first shots were fired by two batteries of the fearsome German 88 cannons. The Italian artillery returned fired, and the ensuing duel destroyed the landscape, slicing through trees and opening deep craters in the earth. After the bombing, which struck a building storing anti-tank mines, exploding and rending the air, a German column of the SS Reichsführer mechanic brigade descended on the Italians of the Friuli Division controlling the bridges and road hubs of Casamozza.

The assault was fast and violent: the German tanks, followed by the infantry, destroyed the Italian roadblocks, forcing the Friuli men to flee. During the retreat, the road bridge over the river Golo was blown up, but the railway bridge was not. The Germans managed to take it intact, and could thus continue their march towards Bastia.

During the battle, the Friuli Division artillery was completely destroyed. In spite of the inevitable defeat, Captain Bruno Conti, the commander of one of the batteries, showed bravery right up until the end, earning a posthumous Gold Medal for military valour. Critically injured in battle, he refused all assistance and for three hours continued to give his men orders in an attempt to hold off the assault. Once he realised that the Germans were about to breach his position and that his death was assured, he urged his men to disengage and flee to safety on the back roads. His uniform soaked in blood, he finally leaned on one of the pieces of his artillery and, alone, let himself die there. The enemy swarming around him was the last thing he saw.

At more or less the same moment, the 10th Mobile Division, of which my grandpa’s unit was a part, was quickly retreating towards the Corsican interior. The order they had received from Magli was to reinforce the airport at Ghisonaccia, on the east coast of the island. But they reached it too late.

The Germans had taken it the previous day, and the Italians stationed there fled hastily towards St Antoine, the mountains and the interior of the island. Second Lieutenant Lucio De Tullio, one of the members of airport command, realised during the retreat that some of his men were stuck inside the airport. Without thinking twice, he went back and somehow managed to get them out. For this action and for the injuries he sustained in subsequent combat, which left him seriously mutilated, he received the Silver Medal for military valour.

The 10th Mobile Division and those who had fled left the airport headed for the Inzecca Gorge, where the Fiumorbo river runs through a narrow passage in the rock, crossed overhead by Pinzalone bridge. Once there, they stopped and prepared their ambush, aware that the Germans were hot on their heels. The Wehrmacht’s goal was likely that of reaching Corte, which was the seat of the Italian high command as well as the storage location of most of their provisions and munitions. It was imperative to halt their advance.

Once my grandpa had received orders from Fucci, he consulted the other officers in his company and they order their men into their defensive positions. Nearby he could see Mazzoni, who had just distributed his squad’s Breda 30 machine guns, which had the unfortunate reputation of being particularly unreliable. But they had no choice but to use what was available.

My grandpa gave his men instructions for the operation, then turned to Borghi. “Whatever happens, stay close to me. Don’t go far”, he said. Borghi nodded, removed the safety catch from his special troops rifle, which had a shortened barrel to make it easier to transport on a bicycle, and loaded the first bullet into the chamber. “I’m ready, Sir” he replied.

They lay in their defensive positions and began to observe the road, waiting to see the head of the German column appear. It was difficult to breathe, and my grandpa struggled to control his shaking hands.

“Not today, Lord, not today, please, not today” he repeated over and over again in his head, like a mantra, thinking of Ginetta’s kisses, his brother’s laugh, his friends from his time in Pola and his parents’ hugs. Lying there, with the possibility that he would die in the next hour, without being able to say anything to anyone, seemed unbelievable. He had to force himself to have faith.

Suddenly, he felt a moment of respite from the tension. “I’ll make it, I’ll come out of this alive” he thought, trying to force his lips into a weak smile. Managing to summon some courage for just a second made him feel better. But at that very moment, the first German vehicles rounded a corner and with a low rumble began to climb towards the Inzecca Gorge. Heading up the column were the tanks, followed by trucks full of troops.

On seeing them, his thoughts stopped abruptly, as if they had smashed against a wall. Something heavy fell over his heart, and time started to slow down, enabling him to register everything with a shocked clarity.

“You know what to do!” he shouted at his men! “Fire until no one is left moving!”.

Fucci’s plan was to hem the German column into the gorge, then finish them off with artillery, whose aim would be directed by observers positioned above the defensive line. A simple but effective design, based on the Italians’ superior knowledge of the terrain.

The German column appeared to be moving, but it also seemed not to be making any progress. My grandpa and his men could not wait for it to be over, but they had to wait even longer, their nerves fraying, until the German vehicles came into range. Staying still and trying to breathe normally was torture. Maddening.

Finally, the Germans reached the ambush position and then, without warning, the valley filled with the deafening crash of hundreds of weapons firing at once. The machine guns took aim at the trucks, ripping through their side panels, exploding their windows and forcing them to a disorderly halt, as if they had been thrown onto the road at random. Later, the first anti-tank missiles were fired, and the first artillery bullets began to rain down on and around the tanks, which came to a halt and began to turn their turrets, searching for a target.

Anyone who is attacked in an ambush of this sort has only two chances of survival. The first is to flee: to get across the ambush zone as fast as possible without looking back. The second is to fight: abandon the vehicles, stand in the road and return fire. The Germans knew this and were well trained. As it was impossible to move under the heavy Italian fire, they jumped out of the trucks and started to fire on the 10th Mobile Division’s positions.

My grandpa emptied the first few magazines as if in a dream, without looking where he was shooting, simply contributing to the volume of shots falling on the Germans stuck on the road. Then distant memories of his training began to come back to him. He loaded the next shot, focused on the viewfinder and this time held his breath before pulling the trigger, to reduce the weapon’s movement, as he had been taught.

He didn’t hear the shot being fired, but the man in his crosshairs performed a clumsy pirouette in the road as a puff of red spread across his grey uniform. A second later he sank to the floor, slumped in an unnatural position. What until a moment before had been a collection of aspirations and feelings became a hollow heap. “What have I done?” he thought, forcing the air from his lungs. In the future he would fire mercilessly, but at that time he was still unaware of how deep into himself he could fall.

His fingers suddenly became cold, and he had the distinct sensation of having crossed into forbidden terrain, stretching out in the dark places on the edges of consciousness, a place where no one should venture. Muddy terrain, where you can sink and never get out. In which the only dimension that counts is that of infinite guilt for the irreparable damage caused.

He did not have time to think about it for too long. The Germans, after the initial confusion, had regrouped and their shots were landing close to the Italian positions. Too close. He realised that many bersaglieri had been injured, as the medical staff were jumping between holes to assist those soldiers that had begun to shout.

Furthermore, the Germans must have managed to warn their artillery, because dangerous fire was being returned from their batteries, coming closer and thundering around the mountains, hastening the moment of retreat.

“Disengage! Get out!” he started to shout. One by one his men began to retreat, leaving the gorge behind them, climbing over the crest of the mountain to find shelter. He too was about to move when on his right he saw Mazzoni leap forward to reach men from other units who were stuck downhill from the German fire. If they stayed put they would die, and someone had to coordinate them and force them to leave. “Where are you going?!” my grandpa screamed at the top of his lungs, but his voice did not reach him.

“Cover him!” he ordered the men still around him, pointing repeatedly at Mazzoni, who was running downhill. Those who heard the order started to fire over his head, in an attempt at preventing the Germans from moving and opening fire on him.

Miraculously, Mazzoni reached the Italian advance positions and managed to coordinate their movements and retreat. For his courage, and for staying in contact with the most exposed Italian units, he was awarded the War Cross for Military Valour.

Two other bersaglieri in the 10th Mobile Division were decorated for their courage that day. Captain Silvino Borla reached the road where the enemy vehicles had been immobilised and took a German non-commissioned officer prisoner. Lieutenant Salvatore Cammarone too, a medical officer in my grandpa’s battalion, who continued to provide aid to the injured throughout the battle and under constant enemy fire.

In the end, Fucci’s plan worked. The Italian artillery improved its targeting of the column stuck in the road and ended the battle. Five tanks and three trucks were blown up in quick succession, along with the men using them for cover and still fighting alongside them. Nothing remained – just a few dark red stains on the road. The rest of the German column, seeing their path obstructed by forces that could overpower them, turned back and returned to the airport at Ghisonaccia, firing in the direction of the Inzecca Gorge to cover their retreat. The 10th Mobile Division units left the valley to shelter from the fire from the German battery and reconvened further uphill.

As quickly as it had begun, it was over. Silence descended on the valley once again, and soon afterwards, night fell, while on the road the twisted remains of the destroyed German vehicles burned. Von Sengler und Etterlin’s attempt to push into the island’s interior had failed and would not be repeated.

When they eventually reached safety, Borghi began to walk next to my grandpa. His eyes were imploring, and he was still visibly shaking. My grandpa noticed his trousers were wet and there was a dark stain running down them. “Don’t worry, it happens. You did well today” he said, squeezing his shoulder. “Nothing else matters. Go and rest now”. He smiled at him and watched him walk away through the trees.

I remember that, as a boy, I convinced my grandpa to play at being my officer in a war game. The piece of wood in my hand became my gun, and with it I ran across a field, from one tree to the next, closing in on my imaginary enemy while he followed me giving me orders on how to move. Suddenly he told me to get on the ground, an enemy plane was about to bomb us.

Unluckily for him, at that exact moment a small tourist aeroplane burst across the sky, appearing from behind the trees and skimming the ground, flying close above our heads. My child’s mind, in which imagination and reality were still closely mixed, was certain that the threat was real, and I started to run screaming towards my grandpa. I reached him in seconds and, in his arms, I finally calmed down. Looking up at him, as he ruffled my hair and dried my tears, I told him that I didn’t want to play at war anymore, it was too scary.

“You’re right, you know, it is too scary. Come on, let’s go home” he said, smiling and taking my hand. At the time I was just pleased that my grandpa thought I was right about something. But now I wonder, over thirty years on, what he was really thinking about when he said those words.

The day after the battle at Inzecca Gorge, the Germans, who had pushed through to Casamozza, came within sight of Bastia.

At midday on the 13th September the Italian artillerymen, once again the men of the Friuli Division, sighted the head of the enemy column approaching and began to fire. The Germans returned fire and stormed the city. The offensive, like the one in Casamozza, was merciless: the Friuli Division was overpowered, panic spread and the Italian troops abandoned the battle field.

By the end of the day, Bastia was back under German control. General Magli, perhaps unfairly furious at the Italian soldiers’ weak resistance, recorded this in his diary: “Evening, Friuli overpowered – Bastia around 7:30pm occupied by the Germans, the Friulis faced a rout! Commander incapable”. The next day he met with General Cotronei, who led the Friuli Division, while he and his surviving men were retreating towards Calvi on the northwestern coast of the island. According to his notes, Magli found him “undone”.

Meanwhile, Nazi high command had set up in Bastia. Its first move was to sack the city for three days, as revenge for the Corsican partisans’ role alongside the Italians, and for publishing pro-Allied leaflets, printed by the mayor, Gherardi. The civilians that had not yet fled tried as best they could to leave the city. Some took to the mountain roads, others were lucky enough to reach their friends and relatives in the surrounding villages.

My grandpa and the troops of the 10th Mobile Division, shaken by their first encounter with the 90th Panzergrenadier Division, waited anxiously for Magli’s orders, while speculating about what was likely to happen next. It was hard to remain clear-headed: my grandpa felt fear snaking around his legs and he had to fight not to let it rise up into his throat. If it got there it would take his breath away and it would become a paralysing panic.

A few days later, on the 17th September, von Senger und Etterlin asked Magli to return the German prisoners of war, threatening to execute 10 Italians for every German if his request were denied. Magli refused to be intimidated and negotiated a prisoner exchange, which the Nazi high command agreed to. But once again, they did not keep their word: all the German prisoners were released, while the Italians only recovered half of their prisoners. Just two days later, to add insult to injury, Corte was bombed by the Luftwaffe, in a clear attempt to take out Magli. The Italian general escaped unscathed, but a few soldiers guarding the headquarters were injured.

However, the situation had become an impasse. The Germans had not managed to move on the interior and reach Corte, but on the other hand, the Italians no longer had the strength to take back Bastia and reach the eastern coastal road.

Both Hitler and the Allies helped to break the deadlock.

Firstly, Hitler ordered his units in Corsica to move to Italy to fight the Allied advance up the peninsula. An evacuation plan was made to get the soldiers out of Bastia through the port and the airport, and German troops began to move northwards, gradually abandoning the southern and central parts of the island. The airport of Ghisonaccia, which had served as a base for the offensive in which my grandpa’s unit fought on the 12th September, was abandoned in the night of the 25th and 26th, whereas Porto Vecchio and Bonifacio had been recaptured by the Cremona Division two days before.

At the same time, between the 14th September and the 1st October, the Allied navy transported French troops from Africa to Ajaccio. That transport operation took place under constant Luftwaffe fire, which managed to sink at least one transport ship full of soldiers. The men who arrived, from the 2nd Moroccan Division, the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division and the 1st Paratrooper Battalion, were for the most part colonial troops, better known as goumiers (from the Arabic word qum, meaning ‘squadron, gang’). The Allies planned to use them for an Italo-French assault on the German positions and for the liberation of Bastia. The operation was to be led by the French General Louchet.

In preparation for this offensive on Bastia, the Allies bombed the city’s airport on the 29th September, rendering it unusable. Forced to restrict their evacuation efforts to the port, the Germans prepared to defend it to the last.

The Allies were planning a pincer attack. The goumiers and the surviving Friuli men would attack from the mountains to the northwest, while other Italian units would advance on Bastia along the coastal road from the south, forcing the Germans to fight on two fronts.

Over the days preceding the attack, the Italian artillery repeatedly bombed German positions around the city. The final assault took place between the 1st and the 4th October. The Italo-French troops advancing from the northwest were met by Germans, but managed to dislodge them from their bunkers in the Teghime hills, which overlook the access route to Bastia. Having lost the city on the 13th September, the Friuli men now fought with courage, to compensate for their previous loss. In 1957, a monument was erected on the summit of one hill, commemorating that battle. However, no mention is made of the Italian contribution: only the French goumiers are praised on the commemorative plaque.

On the evening of the 3rd October the city of Bastia was seriously damaged and lay in flames, having been repeatedly hit by Italo-French artillery. But by then the last surviving Germans, caught in the Allied jaws, were evacuating, having first destroyed any vehicles and supplies that they could not take on board with them. At dawn on the 4th October, a motorcycle bersaglieri squad coming from the south was the first to enter the city. When Italian high command received the news, they immediately called them and demanded that they retreat. The agreement with the Allies was that Bastia should be liberated by the French, and therefore that the goumiers would be the first to parade through the streets.

Thanks to the Italian effort and to that unexpected but effective co-belligerence with their former enemies, Corsica was the first French territory to be completely liberated. This meant that the island was spared the Nazi cruelty that swept through other regions of occupied France and Italy in the following months. The final death count was nonetheless high. Those few days of fighting cost both the German and the Italo-French contingent at least 1000 lives, probably more, as well as hundreds injured on both sides. My grandpa came out of it unhurt.

General von Siegler und Etterlin left Corsica at 11pm on the 3rd October, on one of the last ships to leave the island. Before he left, he refused to comply with Hitler’s order to shoot the Italian prisoners who had fought against the Germans. His case of insubordination was archived by the Nazis on the 5th October and he continued to fight against the Allies in Italy throughout the war of liberation, leading the XIV Armoured Division until the surrender in 1945.

The Wehrmacht survivors who had fought in Corsica reached Italy through the airports in Pisa, Lucca and Pratica di Mare, as well as through the ports of Livorno and Piombino. The Allied air force, which had created a base at Ajaccio airport, pursued them for the entire journey, managing in that period to shoot down 55 German aeroplanes.

When they reached Italy, the 90th Panzergrenadier Division was reinforced and deployed along the Gustav line. My grandpa would meet them there: on the other side of the front, at the battle of Cassino. Hemmed in by the Allies, the division was eventually wiped out in 1945 south of Bologna.

The SS Reichsführer mechanic brigade was turned into the 16th Panzergrenadier Reichsführer Division SS and assigned to contain the Allied landing in Anzio. Over the course of their retreat across Italy, they committed a series of brutal atrocities. The nightmare began in August 1944, when the Division perpetrated massacres in Nozzano (59 dead), Sant’Anna di Stazzema (560 dead) and Vinca (170 dead). The following month, it carried out a raid on the Certosa di Farneta monastery, murdering its prisoners. Then came the turn of Bergiola Foscalina and lastly Marzabotto, where between the 29th September and the 5th October 1944 770 people were killed. In February 1945, the Division was moved to the Hungarian front in order to contain the Soviets. They withdrew to Klagenfurt in Austria and there surrendered to the British, in May 1945. In Corsica, my grandfather had come face to face with a slice of hell.

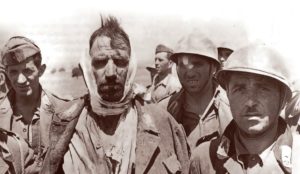

The XXXIII bersaglieri cyclist battalion did not take part in the last assault on Bastia, as they were deployed in the second line. It did, however, enter the city immediately after the French troops, following the units that had pushed the Germans back to the docks of the port. The roads were littered with the remains of vehicles, often with charred corpses still trapped inside. The smell of blood, burnt flesh and death filled the air. Several men in my grandpa’s squad had to stop to vomit before marching on.

The city had been reduced to rubble. Beyond the damage caused by the Allied artillery, the Germans had not trodden lightly either, applying their scorched earth policy to the letter as they left. When the French-Italian troops reached the centre of Bastia, they found the radio station, the port infrastructure and the power, water and gas plants razed to the ground.

As they moved through the city, my grandpa and his men came across the corpses, in an advanced state of decomposition, of the Italian soldiers who had fallen in the battles of the 13th September, when the Germans had taken back the city. The bodies were strewn across the streets, lying where they fell: no one had yet taken the time to move or bury them.

Close to the port were the bodies of the German soldiers killed during the evacuation. Among them, sitting or lying on the ground, were the injured men who hadn’t managed to reach the departing ships. They were awaiting rescue in silence or had resigned themselves to waiting for death.

In that landscape of destruction, my grandpa walked slowly, putting one foot carefully in front of the other, as if in order not to become part of that scene he had to avoid any extraneous noise. After his baptism of fire, he had felt a new feeling growing in him, a hatred of the Germans that was so pure, so profound, that he had decided to cultivate it. Strengthening that hatred would protect him, would enable him to go back home, he thought.

But now, as he looked around on that October morning, he felt his grip on it loosen. He felt his chest being crushed, and suddenly all the fury that had been raging inside him in previous days left him, giving way to an emptiness without redemption, which was gnawing at everyone’s soul, including his.

At a crossroads, he glimpsed an injured German soldier, leaning back against a street corner. He only noticed him because the soldier was looking straight at him. He had a wide red gash on his side, which he struggled to cover with one hand. My grandpa took a brief look at him and realised he wouldn’t live for much longer.

“Go ahead with the others” he said to Borghi, who was at his side. “I’ll catch up with you”.

His orderly looked at him in surprise for a few seconds, then raised his hand to his helmet to salute him and walked on along the road in silence.

My grandpa took two steps towards the German, who continued to stare at him. As he moved forward, he removed his helmet and saw that the other man was lifting a hand to his mouth, with great effort, to mime the action of smoking. My grandpa stopped for a moment to look him in the eye. The man who until a few seconds earlier had been his mortal enemy had a gaze that was drained of any emotion. Nothing was left: not even sadness. He simply looked tired, the tiredness of balancing on the edge of the void.

My grandpa searched in his pockets and pulled out two cigarettes. He lit both of them, sat down beside the German and put one of them in his mouth. As he sucked in the smoke, he felt the soldier’s body lean against his shoulder. He moved a few centimetres closer to him, to support his weight and encourage him to relax. Looking at him quietly out of the corner of his eye, he saw that he was smoking slowly, moving as little as possible, his gaze distant. After a few more puffs, the German’s hand fell to the ground, and my grandpa felt his body suddenly lose its shape.

He stood up, grabbed him under the arms and laid him out on the ground. He stayed looking at him for a few moments, still and without taking a breath. Then he picked up his helmet, threw his cigarette away and headed off to join his unit.

I remember when he told me that story, it was one of the few times he didn’t sugarcoat a war story for my benefit. His eyes went somewhere else, for a moment they became two bottomless black holes.

In the battles he faced in Italy he would not see such displays of human mercy.