Sooner or later life takes youth away from us, like a blanket held on for too long on an autumn morning. My grandpa had to face this moment alone, crushed by the inevitability of war. I, on the other hand, always had him on my side. And in far less difficult circumstances.

It was a cold March afternoon and the cloudy sky was still filled with the smell of winter. After school, my classmates and I went to the traveling amusement park, which in those days had stopped in our city. Our school had given us some free tickets and we rushed to use them, laughing over the metallic rattle of our bicycles.

I was moving from one attraction to the next when a thought suddenly crossed and hit my mind with the speed of an arrow. My dad had been taken.

I remember stopping and looking surprised at my friends. I waved goodbye and left without giving any explanation. I grabbed my bicycle and I got home panting and with my eyes wide open. My dad’s car was abandoned in the garden, just after the garage door, its door open and the keys still in the ignition. It all happened very quickly, I thought.

Raising my eyes, I saw through the house’s windows a group of relatives moving across the living room. Someone was crying.

I already knew what had happened. But I also knew that I could not avoid the cold and metallic taste of words, that I would have had to verbalise what I was seeing. Once I walked inside, I was welcomed by a sobbing summary of the afternoon. My dad had been arrested and nobody knew when we would have seen him again. The television was broadcasting the regional news and with the corner of my eye I saw my father sitting in the back seat of a police car, his profile crossing the screen as he was being taken away.

My mother was sitting on a sofa and everybody seemed lost in their own pain. As I crossed a room filled with blank eyes, I tried to read those faces buried in their hands while thinking about what I could do. I would not have talked about it to anyone. I would have focused on school and my sister only, leaving everything else to my mother. I would have trusted her, my dad and all the grownups around me. And I would have prayed at night.

The only one sharp enough to cut through the confusion was my grandpa. At some point he saw me, got close to me, pulled me in a corner and knelt in front of me. His hand felt heavy on my shoulder and his eyes were locked onto mine. “Now you have to become a man Filippo. It’s time”, he told me. I was twelve years old and his words hit me like a whip, going through my spine with a shiver of fear and pride. I looked at him nodding and his steady gaze pushed his words down my stomach, with the inevitability of an order given to a soldier.

Roughly one and a half months later my dad was released and a few years later he would be found innocent. He had been trapped into the cogs of tangentopoli, the investigations into Italian corruption, without having committed any crime. The event however was not without consequences. His career in the public administration ended, he had to find another career path, our savings ended up in lawyers’ pockets and several acquaintances decided that it was safer to cut all bridges with us. Luckily, my friends never asked any questions and never denied their support. Their heart was bigger than their age and they earned my eternal, although silent, gratitude.

Years later, I would have learnt to look at my dad with great admiration, fascinated by his ability to react without falling into self-pity. But at that moment, I was simply trying to take it one day at a time.

The months following his release were the hardest. My dad was worried, the trial difficult and I could hear him walking nervously around the house at night. At that time, many people involved in corruption investigations were choosing suicide as a way out and newspapers were more than happy to feed readers with endless morbid reports on them. The idea that my dad could do the same in a moment of weakness was gripping my stomach like a cold hand and was poisoning my mind.

The solution was therefore to be vigilant, especially at night. Whenever I heard the floor cracking while lying in bed I would stay completely still under the blankets, to hear whether my dad was trying to open the main door. As soon as I heard the key turning in the lock I was ready to jump out of bed, to stop my dad with an excuse. More than a few times, my dad and I ended up falling asleep on the couch while watching old thrillers, the TV volume low in order not to wake up my mom and my sis, and our eyes meeting without us uttering a word. His hand on my hair was the safest place I knew.

My grandpa never tried to cheer me up in those days. Words often feel weightless among men. But he found a way to make me feel strong anyway. One day he put me in front of a mirror, he grabbed two ties and he started drawing the movements for a perfect knot. I looked at him in admiration, while holding the other tie, uncertain about what to do next. Eventually, I started mimicking his movements until I managed to complete the whole sequence on my own. “It’s perfect, you’re ready”, he told me in the end with a knowing smile. A smile that looked new to me, as it was aimed at a grown-up, rather than a kid. My grandpa, with the rigid posture of an old army officer, had just granted me a promotion.

A couple of years later my dad taught me how to shave, with my great pride. Another step towards adulthood, which I lived with all the exaggerated solemnity of a fourteen-year-old boy. But to this day, every time I dress up before a meeting I go through my grandpa’s motions with the tie, simple movements that instilled new confidence in me.

My grandpa had to let go of his youth, and face a much tougher challenge than mine, on 27 August 1942, when an official bulletin of the Italian War Ministry appointed him second lieutenant of the bersaglieri, an elite unit of the Italian army.

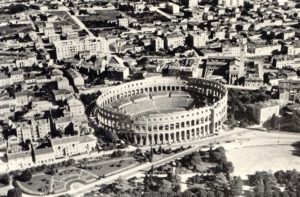

He had joined the army in 1941, when he enlisted for the Officers’ School of Pula, a Croatian city on the Adriatic sea that was, at that time, located within the Italian territory. The training lasted for nine months and ended on 15 February 1942, when he was authorised to go back home in view of his deployment to a war zone.

During that period, spent in the crowded and claustrophobic perimeter of the barracks, he shared a large dormitory with other cadets coming from every corner of Italy. Leaving a perfectly made bed in the morning and wearing an immaculate uniform in the evening were not only daily tasks, but also the key to be granted permission for an evening stroll in Pula. The cadets’ curfew was however at 8PM and familiarising with local girls was strictly forbidden, meaning that opportunities to have fun were, in effect, non-existent. The months in Pula were therefore spent in monkish isolation, with the slow passing of time entirely dedicated to the assimilation and practice of violence.

In that alien space, he learnt how to march and shoot, how to lead men into battle and how to operate several military vehicles, including motorbikes and armored cars. This specific type of training, reserved to mechanised infantry units, gave him the opportunity not to leave for Russia with the ARMIR (the Italian Army in Russia). The first of a long series of miracles that would have helped him to survive the war therefore happened even before he reached the front line. For many Italian soldiers, joining the ARMIR was the equivalent of being condemned to death.

In all probability, my grandpa’s recruitment took place through the Gruppi Universitari Fascisti (GUF – the Fascist University Groups), which he met after enrolling in the engineering faculty of the Bologna University. The GUF were created in 1920 and the Italian Fascist Party, following Mussolini’s indications, had organised them in the attempt of transforming them into the “forge of future Italian leaders”.

Participation in the GUF was entirely voluntary. Members had to be between the ages of 18 and 21, be former members of the Gioventù Italiana del Littorio (GIL – a youth section of the fascist party) and be enrolled in a University or in a higher education institution, including military academies.

My grandpa, who grew up in a country completely filled with fascist rhetoric, had indeed been a member of the GIL. The organisation had been created in 1937 and aimed at supporting the athletic, intellectual and military development of young people, in line with the principles of the fascist regime. The GIL had absorbed the Opera Nazionale Balilla, another fascist youth organisation in charge of organising the so-called campi dux, i.e. sport and military exhibitions which my grandpa joined several times. Enrolling in the bersaglieri required a high fitness level, which my grandpa had developed also thanks to these events.

His desire to join the army as a volunteer, his participation in the GUF, his intention to serve the Italian fascist regime cast a shadow on the way he lived those days. After so many years, it is impossible to know whether his main drive was a naive desire of adventure or rather a deep-rooted political conviction. His motivations are lost in time and in all probability they would have been difficult to decipher even at that moment. The human soul is often the battleground of opposing impulses, both conscious and unconscious, whose understanding always requires a certain degree of approximation.

In those days after all, many of the future antifascist leaders were navigating the same moral dilemmas and negotiating the same grey area of compromise. At that time there was no historical experience of fascism and there were no books describing its hazards and limitations, as opposed to today. Contrarily to those supporting contemporary neo-fascist movements or parties, young people at that time were not blindingly ignoring an already known danger. Director Michelangelo Antonioni, painter Renato Guttuso, writers Italo Calvino and Pier Paolo Pasolini, politicians Pietro Ingrao, Aldo Moro and Giorgio Napolitano, future president of Italy Carlo Azeglio Ciampi and journalist Eugenio Scalfari were, amongst others, all GUF members. My grandpa was definitely not in bad company.

In any case, history was lenient and granted him, as a second miracle, the chance to redeem himself. When he started fighting with the Allies after the armistice of September the 8th, 1943, he risked his life for several months to defeat Nazism and fascism. And he had the bravery of putting his choice to the test during the Italian campaign.

When my grandpa completed his training, Italy was already heading fast towards disaster. Only a few months after the beginning of the war, it was entirely dependent on the decisions of Nazi Germany and there was no theater were Italian units could act autonomously and take the initiative successfully.

Italy’s war started on 10 June 1940, just over a year after the signature of the Pact of Steel with Nazi Germany, when Mussolini thought that the conflict had already been won. Poland had been conquered by Germany and the Soviet Union in less than a month, in September 1939. Denmark was occupied in April 1940, whereas by June 1940 Hitler’s soldiers had already successfully pushed into Norway, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and France. The Wehrmacht seemed unstoppable.

France’s quick collapse had been particularly shocking. On paper, the French army was better trained and equipped than the German one. German generals were actually reluctant to attack France: winning seemed impossible and they repeatedly tried to dissuade Hitler from the project. Only general Van Manstein appeared more optimistic. He developed a new plan, different and bolder than the one used during the first world war and he submitted it to the Fuhrer. His idea was to cross the Ardennes to encircle the French and British units that would have pushed into Belgium to intercept the German offensive.

Hitler decided to approve the plan and the Allies fell into the trap. The Ardennes were considered impassable by modern armored units and were therefore treated as an impenetrable wall. Even when French reconnaissance pilots spotted the huge gridlock created by German vehicles in the Ardennes nobody believed their reports. At that moment, it would have probably been rather easy for the French and British air force and artillery to bomb the enemy columns squeezed on the few roads of the area. But the Allied generals’ short-sightedness blew that opportunity. A war that could have lasted a few days would drag on for five years.

When Italy joined the hostilities, France, after the encirclement and the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk, was about to fall. On the day of the Italian declaration of war, the French government moved from Paris to Tours, after the Germans had crossed the river Seine. A few days later, on 22 June, Germany and France signed an armistice.

Italy’s entrance into war was not only late, but also uncertain. A half-spirited attempt. Despite his aggressive rhetoric, Mussolini was conscious of the fact that the Italian army was not in the best fighting shape. The army chief of staff therefore asked troops not to fight: “The Duce said that it is his intention, with the declaration of war, to change a de facto state of affairs into a legal state, but that he plans to preserve the armed forces, and in particular the army and the air force, for future events”. Basically Mussolini’s decision was supposed to be a symbolic one, taken just to be able to join peace talks with France.

But Hitler had no intention to involve Italy in the talks. Germany had already won on its own and there was no need to share the loot with Mussolini. Seeing a unique opportunity slipping through his fingers, the Duce therefore ordered a sudden attack on the Alps, even though Italian units in that area were only occupying defensive positions.

On 22 June, unprepared and ill-equipped Italian soldiers went to the assault. The conflict with France lasted only 100 hours: Menton was captured but Nice remained unreachable. On 24 June an armistice was signed. The Italians had attacked as if they were still fighting the first world war and in a few hours, for no reason, 631 soldiers had lost their lives. France, on the other hand, lost 37 men.

In order to score some military success that would legitimize him as a credible ally of Nazi Germany, Mussolini then embarked in the infamous Greek campaign, after having considered other potential war theaters, from France, to Yugoslavia, to Tunisia.

Once more, like in France, the Italian offensive was improvised. Launched in October 1940, it was quickly halted. Already a month later, the Greek counterattack pushed the Italians back into Albania, from where they had started. A new Italian attack in March 1941 managed to achieve only negligible results, while costing 12.000 men between dead and wounded. A disaster. Mussolini himself realised the gravity of the situation and, from that moment on, ordered the army to maintain a purely defensive formation.

Hitler was livid. The Germans were preparing the invasion of Russia, but they were forced to postpone it and intervene to secure their shaky southern flank. In April 1941, the Nazis therefore rushed into Greece and Yugoslavia, which were defeated in less than one month.

On 10 June 1941, precisely one year after Italy’s entrance into war and with the hostilities ceased in the Balkans, Mussolini declared: “It is absolutely certain that in April, even if nothing had happened to change the situation in the Balkans, the Italian army would have overwhelmed and annihilated the Greek army”. Reinventing reality had already become indispensable.

This was all the more necessary because, in the meantime, the position of the Italian army had badly deteriorated also in northern Africa. The conflict with Great Britain, started in June 1940, had been so disastrous that already in February 1941 Hitler had been forced to send General Rommel and his Afrika Korps to support the Italians, who were on the brink of a crushing defeat. The entire 10th Army had indeed been annihilated and the British had reached El Agheila, in Libya, at the southern end of the Gulf of Sidra. From December 1940 to February 1941, the British had lost 500 men but had captured 130.000 Italian soldiers. One of them was Enzo, my grandpa’s brother. He would have spent the remaining war years in India, in a British prison camp.

“A nation that for sixteen centuries behaved like an anvil cannot, in a few years, become a hammer”, was Mussolini’s scornful comment on the catastrophic performance of the Italian army. In his mind, it clearly wasn’t his fault. It was the fault of all Italians.

Such an embarrassing sequence of defeats pushed the Duce to beg Hitler, who by then considered him more as an obstacle than an ally, to help him with the invasion of Russia. Mussolini was indeed looking for any opportunity to regain prestige with Nazi Germany. And he did so, once again, by gambling on the lives of Italians. Official records indicate that out of the 235.000 soldiers sent to Russia from July 1941, 114.250 became casualties. Almost half of them.

Finally, in November 1942, the Duce thought he could change his fate. Hitler had indeed decided to invade the whole of France, including the Vichy regime. His plans dictated that Corsica had to be occupied by Italy, also because of the presence, in that region, of an irredentist movement that could provide some support, at least in the beginning, to Italian troops. Mussolini could finally feel useful again.

He thus decided to go big. And he sent 69.000 soldiers to Corsica, whereas the island had a population of 220.000 people. An absolute exaggeration. But, as always, the Italian army could not keep up with the ambition of the Duce. In order to land troops in Corsica, the navy therefore had to rely also on “motosbarchieri”, capable of transporting 15 men each. An euphemism to indicate fishing boats.

“Crazy stuff”, wrote the Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano in his diary when commenting on the landing. A man that symbolises the grey area of constant compromises in which many people had to live in those days. He was a member of the fascist party, but he was also critical of it. And his remark on Corsica, together with others, would eventually prove fatal for him. After the armistice with the Allies, Ciano was arrested in Verona by the SS and accused of high treason for having advocated the end of the fascist regime. He was condemned to death and shot in the early hours of 11 January 1944.

His death caused a bitter family feud. Ciano’s wife, Edda, was one of Mussolini’s five children. Her intercession with her father, however, could not save his life. And neither could her attempt to trade her husband’s life with his diaries. When judge Vecchini asked whether it was really necessary to kill Ciano, even though he was his son-in-law, Mussolini simply replied: “Do your job”. A decision that was approved also by Rachele, Mussolini’s wife and Edda’s mother. Many years later, after the end of the war, Edda will declare that she had forgiven her dad for not having saved Galeazzo’s life. When asked about her mother, she will just say: “She defended her man, I defended mine”.

My grandpa, recently appointed second lieutenant in the bersaglieri, was one of the 69.000 soldiers that landed in Corsica thanks to the “motosbarchieri” gathered at the last minute. His war was beginning in Italy’s darkest hour. And it would have been much longer and bloodier than he could have imagined.

Wonderful. Thanks Filippo. It is a great job that you’re doing.

Thanks a lot Andrea! Much appreciated 🙂