Translated into English by Aimee Van Vliet

A train journey

The first time I left home with no intention of returning, or at least not immediately, was with my grandpa.

Rovigo is a small, quiet town, which seems to have been asleep since the beginning of time, while the world hurried around it, rushing about in some mysterious other place. As a boy I loved its quiet, the fact that I could cycle across town alone, the landmarks I would use to find my bearings, so well-known and unchanging. On a hot summer’s night, only silent stillness reached me through my open bedroom window, occasionally interrupted by the noise of a train passing on the nearby Padua-Bologna line.

My eyes closed and my head on the pillow, I had learned to expect the rhythmic beating of those metallic wails, daydreamed about those powerful machines that could move so quickly from one place to another while everyone slept, opening doors to unexplored worlds and unseen cities.

After some time I had managed to convince my grandpa to take me to the train station to watch the trains coming and going, fascinated as I was by their mechanical parts and by the people who seemed to board them every day, moving through their lives as if it were the most natural thing in the world. To me it remained a mysterious wonder.

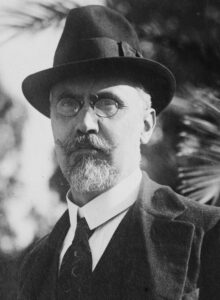

I remember my long walks up and down the two station platforms in Rovigo, my eyes fixed on the rails and on the manoeuvres of the carriages, the impatience in my legs as I waited for the next train, my grandpa’s solid hand around mine. On those long afternoons, each one the same as the next, he must have had infinite patience with me. And yet I never felt, not even for a second, that he would rather have been somewhere else, as if the best way he could spend his time was to share in my sense of wonder. I realise now that given his propensity for solitude, he was likely happier and calmer in those empty stretches of time than I could ever be.

On one of those afternoons, while I was eating an ice cream distractedly in the sun, I experienced the unexpected joy of seeing a train pass through the station at high speed without stopping. The loudspeakers had given a crackly announcement and my grandpa got me to step back from the edge of the platform, placing me behind one of the pillars that supported the roof. I had looked at him, smiling, thinking that he was being overprotective. But a moment later, the high-pitched whistle of the train filled my ears and the blast of air pushed back by the carriages stung my eyes.

My mouth hung open as I watched the train shoot past, forgetting about my ice cream and everything else around me. Speeding past me like that, the train looked like some kind of metallic monster, possessed by an animalistic fury. It had scared me, but I was also transfixed. In just a few seconds the entire convoy had whooshed past, and I watched the last carriage until it disappeared around a bend on the horizon, my eyes glued to the red lights glowing on the rear buffers.

“I wonder what you can see of Rovigo station from inside the train!” I had said to my grandpa, almost shouting in excitement. “I’m sure it looks very small”, he said with a smile.

From that day onwards I started to ask my grandpa to take me to see that train passing through as often as possible. I was curious about everything: where it was going, where it was coming from, how much the ticket cost, how you got on, how fast it went, how many people were in it. I had so many questions and I repeated them over and over again, and my grandpa tried, as much as he could, to satisfy my thirst for knowledge.

One day, probably worn down by my insistence, he suggested that we take that train, to see Rovigo station shoot by through the window. I hadn’t even realised that such a thing was possible, and when my grandpa suggested it I was momentarily speechless. “Yes! Let’s go!” I exclaimed, throwing my arms around him. My grandpa picked me up off the ground to hug me and it seemed like his eyes were shining as brightly as mine were.

So it was that one sunny morning he came to collect me, I got into his car and I left Rovigo behind with the firm intention never to return, or at least it seemed that way in my child’s mind. During the car ride to Padua I watched the countryside roll by through the car window as we sped along the motorway, and I held my breath, feeling that I had embarked on a voyage of discovery that no one else had yet undertaken. In my mind, reality and fantasy still coexisted in perfect harmony, creating a dimension in which it was absolutely plausible for me to leave home forever, or at least on a journey far away. Surprisingly, I felt no fear at the prospect: the curiosity and excitement of leaving the comfortable confines of my town took over. The solid presence of my grandpa at my side was all I needed to feel safe and calm.

At Padua station we got on what at the time must have been an Intercity, linking Venice and Rome and only stopping at the main stations. We took our seats in our compartment and my grandpa had to tell me several times to stay in my seat. I was worried that I would miss the moment when we would fly through Rovigo station and I didn’t want to take any chances.

After what seemed like an eternity, we finally got close to our town, and my grandpa told me to go next to the window. I didn’t need to be told twice, I jumped up and gripped the window ledge, standing on my tiptoes, the cold glass pressing on my nose. After checking several times that I was on the right side of the train to see Rovigo, I focused my eyes and waited to see my town whizz by in a few seconds.

In my mind I still have a snapshot of that moment, distorted by speed: the red brick station building whistling past before I could focus my eyes on it. Faced with that image, I felt like an astronaut being shot into an unknown space, on board a fantastic machine. I turned to my grandpa, feeling as brave as the most hardened explorer, my mouth drawing a perfect circle of awe. My grandpa smiled and ruffled my hair, visibly pleased that I was as impressed as he had hoped.

When we got to Bologna, we got off and waited for the next train back. It was the first time I had ever been in a station like that, even bigger than Padua, and with no warning I was thrown into a cacophony of announcements and screeching trains, while a crowd of passengers swirled around me, moving chaotically between trains. I hadn’t expected this human spectacle, and all I could do was pull my grandpa this way and that, as if I were checking that it was all really happening. For the first time, I had the impression that I was living in a big world, with so much to discover, and that it would be worth leaving the place I was born to visit it all. I wasn’t yet entirely conscious of those thoughts, but that day I began to sense that the horizons of my town were not the only ones available. That feeling would stay with me, and years later it helped me, or maybe pushed me, to leave my town and my country to see whether a life lived elsewhere matched the image of it in my mind. One sets off with the lightness of fantasy and one returns, or stays, filled with the weight of reality.

When the train to Padua pulled up at the platform, my grandpa and I took our seats and headed home. I saw Rovigo station once again disappear through the train window, although by then tiredness was replacing awe. By the time I reached my grandpa’s car I was exhausted by the emotions of the day, and I fell asleep at his side, while he drove me home in silence, taking care not to wake me. When we got home, he handed me off to my mum and I said goodbye with a long hug. I walked away, my eyelids heavy, holding a new piece of the world in my hands.

Arrival at Lanciano

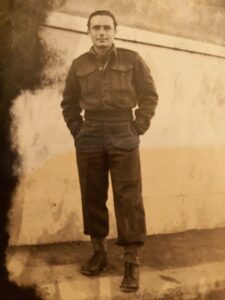

The journey that my grandpa took after the collapse of the Gustav line and the end of operations in the Mainarde mountains brought him no satisfaction, nor did it enrich him with new experiences or emotions. Once the Italian contingent had arrived at Picinisco, which was the last stage of the Italian Liberation Corps’ advance, he and the other soldiers were transferred to the Adriatic sector to continue their fight against the Germans.

Exhausted from days of combat and marches through the mountains, he threw himself down onto the dusty flatbed of a military truck and was carried, sleeping, to Lanciano, unable to imagine his future and what it had in store for him. Throughout the clanking journey across the Apennines he tried to rest as much as possible and not think too much about either Ginetta or Borghi. He felt as if he had a barrel instead of a body, that was now full to the brim, unable to take on even the smallest drop of extra emotion. Only emptying his mind seemed to bring him some relief, and so he tried to concentrate on that, while he kept his eyes stubbornly shut and let his limbs absorb the bumps of the truck bouncing across the badly damaged roads of central Italy.

While General Utili’s men were being transported to their new area of operations, allied command sent out the following communiqué, officially recognising the contribution of the Italian Liberation Corps (CIL) on the Gustav line: “Troops from the Italian Liberation Corps, made up of regular units of the Italian Army (…) advanced 8 kms across the rugged mountain terrain of the Abruzzi National Park to occupy the town of Picinisco, 17 km north of Cassino. The Italian Corps was on the allied line for the last two months (…) and achieved considerable success in driving enemy forces back from Monte Marrone.”

This recognition was a prelude to the enhanced role that the Italian contingent would play from that point onward in the Italian campaign. The Normandy landings and the forthcoming landings in Provence, planned for the 15th August 1944, would indeed divert many of the British and American units in Italy. Those units were gradually and partially replaced by Italian soldiers. On the 3rd June, General Alexander, Commander of all allied forces in Italy, had informed General Messe, the Chief of Staff of the Italian Co-Belligerent Army, that after Rome was liberated the Allies would rely much more on the Italians to continue the war effort. For that reason, the upper limit of 14,100 men initially put on the CIL was permanently removed, demonstrating the Allies’ newfound trust in their former enemies.

While it was being redeployed to the Adriatic, the Italian contingent began to receive reinforcements and was joined by the Nembo Paratrooper Division, which merged with the 184th Paratrooper Regiment already under Italian command.

Utili therefore found himself in charge of forces which, including the units that would arrive in July, the Monte Granero and Grado battalions, would reach the impressive size of an Army Corps of around 20,000 men. To better manage them he reorganised them into two divisions: the Utili and the Nembo.

The Utili division, the successor of the Motorised Grouping, was made up of two brigades. The first included both the 4th Bersaglieri Regiment, made up of the 29th and 33rd Battalions, in which my grandpa served, and the 3rd Alpine Regiment, which included the Monte Granero and Piemonte Battalions, the heroes of Monte Marrone. Ettore Fucci, who had led my grandpa and his men ever since the fighting in Corsica, was put at the head of the first brigade. The second brigade was made up of the 68th Legnano Infantry Regiment and the San Marco Navy Infantry Regiment, including the Grado and Bafile Battalions.

The Nembo Division was less varied, being made up of the 183rd and 184th Paratrooper Regiments, as well as the 184th Paratrooper Saboteur Battalion.

Besides these two divisions there were also the artillery and engineering units, as well as the 9th Assault Unit.

The CIL’s deployment in the new sector was completed on the 7th June, and the very next day General Allfrey, the commander of the 5th British Army Corps, commanding the Italian contingent, ordered an attack across the entire front.

My grandpa barely had time to recover from the recent battles on Monte Marrone and his uncomfortable 150 km journey to Lanciano, before it was time to gather troops and equipment to prepare for another advance. The Germans were retreating, and it was imperative to keep up the chase, not to give them a moment’s peace.

As he walked among the parked trucks, patting the dust from his uniform, he was joined by Mazzoni, another second lieutenant in the 9th Bersaglieri Company, a former classmate from officer training college in Pola and present on every battleground from Corsica onward.

“Sorry to hear about Borghi” he said, stopping him and placing a hand on his shoulder. “How are you?” he asked.

My grandpa looked down at his boots, embarrassed. He wasn’t expecting such a personal question and, not knowing how else to stall, he began to roll up the sleeves of his uniform. “I don’t really know. I’m tired, I think”, he said. He raised his gaze to look at Mazzoni, who stood before him, waiting for him to say something more. My grandpa sighed and looked down again. He paused for a moment before going on, to make sure that his voice would not crack. “Honestly, I don’t know what to do” he said at last, in a whisper.

“Sometimes all that’s left to do is to have courage. Be brave with ourselves” said Mazzoni, squeezing his shoulder and tilting his head to try to meet his gaze. My grandpa noticed and looked at him, feeling that his eyes were dangerously close to filling with tears. “I’m here if you want to talk, remember that” Mazzoni added with a smile.

My grandpa struggled to swallow and nodded, but his lips were tight and his forehead was furrowed with wrinkles that looked older than even he did. They stood in silence for a few moments. “You’ve changed, Adolfo. You talk less than you used to” Mazzoni said. “It must be this war”, my grandpa replied, starting to move away and faking a smile in an attempt to end the conversation. But as he moved one foot in front of the other he realised he had something inexplicable lodged in his ribs. Attempting to explain it was as useless as trying to give a shape to sand. Who can truly say what is happening inside us? It was easier to ignore reality than to let it overwhelm him.

To his relief, the new operations started up quickly, between 1 and 2pm on the 8th June. He finally had a new mission, something to focus all his attention on, so that he could forget the past and the future. He now knew that fear cancelled time, transporting men into a pure dimension without feelings, in which only an eternal, cold present could exist. A place in which, given the circumstances, he could almost say he was happy.

Everything was in place to begin pursuing the Germans northwards.

Political turmoil

While the CIL was returning to action in Abruzzo, in Rome political scores were being settled. Both King Victor Emmanuel III and Badoglio hastened to salvage some dignity that June, attempts that were destined to fail.

The King, on the 12th April of that year, had broadcast a radio message in which he announced his decision to appoint his son, Umberto II, as Lieutenant General of the kingdom, once Rome was liberated. His stepping aside was seen by everyone as an essential step towards saving if not himself, then at least his house, which by that point was indissociably entangled with fascism and guilty of a hasty transfer to Brindisi, seen by most as a cowardly escape.

Benedetto Croce himself, at the start of 1944, had said: “As long as the current King remains as head of state, we will feel that fascism is not over, that we remain caught in it, it will continue to corrode and enfeeble us, that it will reappear, more or less disguised.” His was a viewpoint that many shared.

Before handing over power, though, Victor Emmanuel III tried to scrub some of the grime from his recent past. First, he tried to take credit for the plot to overthrow Mussolini, declaring in his notes that his single-handed action against the regime, which was “hindered by the state of war, had to be meticulously prepared and conducted in the strictest secrecy, upheld by those who came to speak to me about the discontent in the country”. Obviously, no one believed him.

Given that that road was closed to him, he tried to make sure that the transfer of power to Umberto II took place in Rome, to mark his more or less glorious return to the capital. That return was denied him, however, given that the antifascist world looked on Victor Emmanuel III as nothing more than an absconded king and accomplice of Mussolini. After some vacillation, he was forced to sign the decree transferring powers to his son immediately and with no further conditions. He eventually signed it on the 5th June in Salerno, and from that day forth Umberto II was invested with his father’s privileges, although Victor Emmanuel kept the title of King for himself.

A few days later, on the 8th March, Badoglio too was called on to pay penance for his actions.

As soon as he had been appointed Lieutenant General, Umberto II flew to Rome and ensured that a delegation from the Badoglio government, still based in Salerno, met with representatives of the various antifascist forces that had emerged in the previous months. The meeting took place at the Grand Hotel, in the same room where Mussolini had formed his first government after the march on Rome. The meeting had just begun when Badoglio was told in no uncertain terms that his political career was over and that all that remained was for him to tender his resignation and pass the baton to Ivanoe Bonomi, who had received the support of the parties gathered there. Badoglio’s fate, which was tied to the King’s with a double knot, as well as his failure to oppose the Germans immediately after the fall of fascism, was sealed.

Once Badoglio had considered the situation, he resigned, but before taking his leave he spewed vitriol against the CLN politicians gathered before him: “Here you are around this table (…) not because you, who hid or shut yourselves in convents, could have done something – those who have worked until now, taking on the gravest of responsibilities, are military men who belong to no party”. Whether he was right or wrong, no longer mattered – political expediency required a new face to lead the government.

When Churchill was informed of the political upheaval, he protested vehemently and tried to intervene to influence events. His comments on the situation were not flattering: “It is a great disaster that Badoglio should be replaced by this group of aged and hungry politicians. He has been a useful instrument to us from the times when he delivered the fleet, in spite of the enemy, safely into our hands. (…) Instead we are confronted with this absolutely unrepresentative collection”. An undoubtedly cynical point of view, probably motivated by his famous and visceral anti-Communist views.

In spite of these British protests, however, the Allies did not lift a finger to interfere in Italian politics. Roosevelt, after initial hesitation, eventually declared that “it would be a grave mistake not to allow the swift announcement of a Bonomi government.” The British, through gritted teeth, finally accepted the situation, demonstrating that London no longer had its hand on the allied coalition’s rudder, and had not for some time.

The new government took up its functions in Salerno on the 22nd June and was given authorisation by the Allies to move to Rome in mid-July. It lasted until the 26th November, when Bonomi was forced to hand in his resignation to the Lieutenant due to the increasing tensions between leftists and moderates in his government. One of the controversies surrounded an interview given by Umberto II to the New York Times on the 7th November, in which the Lieutenant declared that the choice of an Italian institutional set-up, in other words the choice between a republic and a monarchy, would be put to a popular vote. Bonomi was accused of helping Umberto II to prepare his statements, thereby deviating from the political line established by his government in June, which was to give that decision to a constituent assembly. The left wing preferred to avoid a popular vote, as they were aware that the monarchy could use emotional manipulation to garner support. Not to mention that holding a referendum would allow certain parties, in particular the Christian Democrats, to abstain, avoiding taking a position on such a delicate subject.

The Lieutenant decided to open consultations to form a new government, attracting a great deal of sniping. His actions, while institutionally correct, ran up against a CLN that was unhappy to see an important political transition managed by a representative of the House of Savoy. In the end, Bonomi was restored, this time without the support of the Socialists and the Action Party and was sworn in on the 12th December 1944.

The second Bonomi government remained in office until the end of the war and was dissolved on the 12th June 1945.

During the same period, the resistance had become more solidly organised and was by then a considerable problem for the German army in Italy. The Voluntary Freedom Corps (CVL in its Italian initials) was established in Milan in June 1944, becoming the first structure to coordinate partisan forces and gain the recognition of the Italian and allied governments. The supreme command of the CVL was entrusted to General Raffaele Cadorna, while the Action party’s Ferruccio Parri and Communist Luigi Longo managed operations.

At the same time, allied supply launches had come to reinforce partisan units, enabling them to perform their tasks more effectively. This support was given not without hesitation and disagreements. Most of the supplies were indeed distributed by the British, who were torn between their desire to wage an intense fight against the Germans, involving as many partisans as possible, and their desire to curb the formation of Communist powers. Cadorna had received an instruction leaflet saying: “As long as every organisation can demonstrate its ability and rapidity in performing offensive actions against the Germans, we are not interested in their political motivations.” However, it continued, “where political tendencies interfere with the organisational and operational plans that are an essential part of the Allies’ advance through Italy, assistance will not be provided through this Headquarters”.

The CIL advance

All these events, however, barely skimmed my grandpa’s reality. Permanently attached to his gun, his eyes constantly on his men and the probable enemy positions, his life consisted of much more simple and immediate concerns, such as sprinting after the Germans, food swallowed hurriedly during transfers and a primal attachment to life. His days now consisted of little more than tiredness and adrenaline, which had frayed his nerves and left him so wired and febrile that rest was impossible.

As soon as they received the orders to advance, on the morning of the 8th June, the same day Badoglio resigned, the Nembo Division sprang forward and occupied the towns of Crecchio, Canosa, Sannita and Orsogna, fortunately without encountering any opposition. To the left of the Italian deployment, the 68th Infantry Regiment and the 9th Assault Unit had been slowed down by the Germans. These, though, were rearguard manoeuvres linked to the retreat from the Gustav line: the enemy had no intention of staying. Having exchanged some mortar and automatic weapon fire, the Italians had managed to press forward, and on the 9th June, enter Guardiagrele.

Then, they passed the baton to the 1st Brigade of the Utili Division, in which my grandpa was serving. Having passed the other CIL units, they threw themselves into the race northwards, taking advantage of the confusion among the German troops at that time. The alpine units then took Cascanditella, while my grandpa and the bersaglieri advanced further, entering Bucchianico, on national road 81, which in the past was known as Via Viscerale, leading straight to Chieti.

Not stopping to take a breath, the Nembo Division caught up with them, leapfrogged that town and by the evening of the 9th June managed to rush into Chieti. According to the Allies’ plans, the liberation of the town should have been the responsibility of the 4th Indian Division, but the paratroopers had not wanted to wait, and they overtook the advance on their own initiative, effectively surprising the remaining German defences. As they came to the town centre, the civilian population poured out onto the streets and welcomed them in triumph. Chieti became the first Italian of a certain size to have been entirely liberated by the Italian contingent, and it was a moment of high emotion.

Those days were the beginning of a new phase in the CIL’s war effort. After the rather static period spent in the Mainarde mountains, this was a sudden sprint northwards, which would only come to an end once they reached the Gothic Line, the last fortified line of German defence in the north of Italy. The line, which snaked for 300 km across the Apennines, went from the province of Massa Carrara on the Tyrrhenian Sea to the city of Pesaro on the Adriatic. With its casemates, machine gun nests, bunkers and minefields, it bogged down the allied offensive for months, until the final offensive was launched in April 1945.

On the one hand, the rapid advances that the CIL saw in the summer of 1944 contributed to improving the soldiers’ morale, but on the other, the kind of movements it required exhausted them physically, with ever longer marches. The CIL trucks were old and limited in number, spare parts hard to find and tanks completely absent. Every move required the soldiers to march for tens of kilometres, all their equipment loaded on their backs, and with boots that in many cases were starting to wear through. The situation was made even trickier by the actions of the Germans, who were applying a scorched earth policy as they retreated. Every bridge, every logistics hub was destroyed, while every house, path or body they left along the way was mined, to draw the Allies into an endless series of booby traps and force them into the long, frustrating task of demining liberated territories. Landmines set by retreating German troops continued to cause military and civilian casualties in Italy until at least the 1950s.

Having taken Chieti, Utili set up his headquarters there. He launched a difficult chase after the Germans, in an attempt to inflict the most possible losses on the departing enemy. This was a difficult objective, given the scarcity of transport, the destruction of the roads and the speed with which the Germans withdrew. The CIL units were scattered, and on the 11th June they entered Sulmona, L’Aquila on the 13th and Teramo on the 15th, hotfooting it across Abruzzo but failing to engage the Germans in battle. Of course, the German rearguard actions continued and there were frequent exchanges of fire with the departing soldiers. A constant stream of dead and injured men flowed into Italian field hospitals, filling them with the unfortunate victims of a series of skirmishes, forgotten by men and by history. However, every setback faced by the CIL in that period was short-lived.

On the 17th June, the Italian contingent once again switched position within the allied forces, leaving the 5th British Army Corps and coming back under the command of the Polish Corps. Utili and Anders were back together again, having said goodbye months earlier on the Mainarde mountains, shortly before the final offensive on the Gustav line.

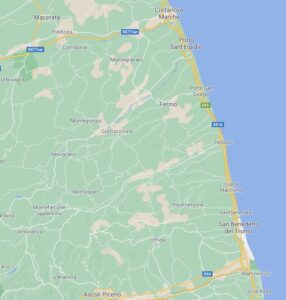

Anders immediately set out his next target: the liberation of Ancona and the occupation of its port, which was of huge strategic importance for the allied logistical effort. The plan was for the Polish Corps to head straight for the city, following national road 16 along the coast. The CIL would advance inland, protecting the Polish contingent’s left flank.

To execute the plan, the Nembo Division was immediately launched northwards along national road 81, and on the 18th June entered Ascoli Piceno, breaking through to the Marche, while the fleeing Germans were hindered by particularly threatening and fierce partisan gangs. They would strike the retreating columns, even managing, in a few cases, to take German soldiers prisoner.

Between the 21st and the 22nd June, the CIL finally managed to reach at least a part of the enemy rearguard, forcing it to stop and engage in a series of skirmishes in the province of Macerata, close to the towns of Sarnano and Colbuccaro.

In order to keep up the advance towards Ancona, they would have to take the town of Macerata, which was immediately to the north of the Italian positions. The relatively easy advance of the previous two weeks had lulled them into a false sense of security, however. This time the Germans had actually decided to stop and fight, and had holed up along the Chienti river, just south of the town. On the 26th June, the Nembo Division attempted a crossing, but quickly had to give up and withdraw: the enemy opened fire with mortars and machine guns, and easily mowed down the first lines of paratroopers who had gone into the attack.

It was a traumatic blow for the CIL, which then stopped to re-evaluate its plans, having been pinned down for the first time since operations began in the Adriatic sector. Macerata finally fell on the 30th June, simply because the Germans, who were being chased in all directions by the Allies, advancing across all sectors, decided to continue their retreat so as not to be surrounded. Local partisans told the Nembo Division about the enemy retreat and the paratroopers entered the town, engaging the last departing German patrols in battle. Once again, the Italian troops were welcomed joyfully by the liberated civilians.

At that point, to avoid dispersal of the Italian contingent, the Polish high command ordered Utili to gather his troops before continuing their advance, given that their lack of transportation had forced some CIL units to lag behind the advance positions that the Nembo paratroopers had reached. Given that order, Utili complained: “The lack of transport is particularly dire as it forces some magnificent units, which are growing in capability, into a support role. Given the right vehicles, they could have a far greater impact.”

The battle of Filottrano

Once they had gathered their forces, the CIL should have headed to Jesi to occupy it, to establish a defensive position to the left of Ancona and allow the Polish contingent to advance and take it. However, to reach Jesi they had to cross the village of Filottrano, which the Germans had turned into an effective defensive fortress, thanks to the thick walls of its buildings and its dominant position over the surrounding countryside. Filottrano is built on an outcrop around 300m high, surrounded by agricultural land and small tree-lined roads. The red buildings, seen from the hills around the town, are a jagged skyline set against the backdrop of the Apennines. Utili looked at that line with apprehension, having received the inevitable order from Anders to take the town.

The task of assaulting Filottrano was once again assigned to the men of the Nembo Division. Paratroopers began their manoeuvres to approach, and deployed along the Fiumicello river, which runs just south of the town. Here they were immediately engaged by the Germans and were forced to hold off a bloody counterattack during the night of the 3rd and 4th of July.

Having checked the soundness of their position, Utili gave orders to attack. The plan was to attack the town simultaneously from the south and the east, with the support of both Italian and Polish artillery and some Sherman tanks from the Polish Kresowa Division.

The attack was finally launched at dawn on the 8th July, after initial artillery shelling. The Italian command considered the option of involving the allied air force but decided against it. There were still many civilians barricaded inside the buildings and cellars, and the risk of unnecessary bloodshed if the bombing was too heavy was unacceptable. The job of dislodging the Germans, then, fell entirely to the soldiers of the CIL.

As soon as the paratroopers approached the town, they came into contact with enemy troops in greater numbers than they had expected. Two infantry battalions were holding Filottrano, from the 71st and 278th Wehrmacht Division, equipped with three tanks, five armoured vehicles and various anti-tank weapons.

The German 71st Division had fought in Stalingrad and had been completely decimated at the beginning of 1943. Rebuilt during the summer of the same year, it was sent to Italy only to face almost the same fate at the battle of Cassino. What was left of the Division retreated to the Gothic Line, to then be transferred to Hungary in an attempt to contain the Soviets. At the end of the war they surrendered to the British close to Klagenfurt, in Austria. The 278th Division, however, focused its efforts on defending Ancona and was then redeployed to the Gothic Line. The end of hostilities caught them at the Brennero Pass, which they had been sent to hold.

The conflict around Filottrano raged for a full day on the 8th July, under clear skies and a blazing hot sun. Again, just like during the first German counterattack on Monte Marrone, my grandpa found himself watching powerless as tracers ploughed into the horizon, setting it on fire, while the roar of the explosions ricocheted through the countryside, turning his stomach. He could do nothing to help the paratroopers in trouble and he stood watching the scenes of destruction as if hypnotised, his fierce joy at not being in immediate danger mixed with a ruthless feeling of guilt, leaving him confused and worn out.

During the assault, two allied tanks heading for Filottrano from the east were destroyed by cannon fire and German anti-tank mines, close to what would become known as the ‘crossroads of death’, and that today has been replaced by a roundabout at the eastern entrance to the town. One of the tank drivers, once his vehicle had been hit, tried to escape from the blazing metal trap that his Sherman had become, but as soon as he opened the top hatch he was mown down by German machine gun fire. His legs still stuck inside the tank and his torso hanging down from the turret, he was left dangling appallingly in a void. Slowly, the air filled with the acrid smell of burnt flesh.

The infantry following the Sherman tanks did manage to advance, firing, and holed up a little further along, inside the hospital building, and were immediately targeted by German artillery. The units trying to enter Filottrano from the south were stopped by the enemy’s furious resistance before they had even reached the town. German soldiers shot along streets and from windows, they fired at the access points to the town from machine guns and armoured vehicles and filled the sky with the lethal arcs of their hand grenades. No corner was safe.

In the evening, under continuous German artillery and tank fire, the paratroopers were forced to abandon their positions and retreat. The only remaining option, in spite of their tenacity, was to survive, reorganise and try again the following day.

At that point, the Allies again suggested razing the town to the ground, but in spite of the difficulties and the pressure that General Morigi, the commander of the Nembo, was under, he was again steadfast. Given the choice between risking civilian lives or military, Utili and Morigi chose the soldiers, even if it meant giving up on an easier victory. And their men did not object.

Luckily for the CIL and for the residents of Filottrano, the Germans received orders to abandon the town during the night, in part due to the losses they had suffered, and they crept out of town under cover of darkness. On the morning of the 9th July, Filottrano fell into Italian hands. Paratroopers began to patrol the streets of the town, scarred by the fighting, and bring the civilians out of their underground hiding places, from which they emerged dirty and hungry, in some cases having been in hiding for an entire week. Then they reached the tower of the aqueduct and raised the Italian flag. That flag is today kept in the town hall.

The battle of Filottrano cost the Nembo Division over 300 men, between the dead and injured. But the Germans, too, left many soldiers on the battlefield, as well as losing over fifty men who were taken prisoner by the Italians during the battle. The bravery shown by the paratroopers in that sector did not go unnoticed. General Leese, the commander of the 8th British Army, wrote to Utili: “I learned with great pleasure about how your men acted brilliantly during the difficult fighting that led to the taking of Filottrano (…). I personally believe it to be a great achievement to (…) have an Italian contingent: the actions of this contingent will contribute greatly to the prestige of Italy”.

Crossing the Musone

Filottrano had been taken but it was not yet time to rest. The main objective of the advance was still Jesi, which had to be taken in order to protect the Polish contingent’s left flank as it advanced towards Ancona.

The Germans who had defended Filottrano had retreated, but they had not gone very far, settling just north of the Musone river to cut off the road to Jesi. In the short time available they had managed to mine it and turn it into a good defensive line, which the CIL would have to break through.

The Nembo Division desperately needed to rest after the battles of the previous days, and was therefore replaced on the frontline by other units of the Italian contingent. Utili distributed orders and the assault on the river was given to the 68th Infantry Regiment on the right, close to the village of Casenuove, and to the 33rd Bersaglieri Battalion in the centre, close to Castelrosino, along the provincial road (former national road) 362, known as ‘Jesina’, which headed directly north to Jesi.

On the evening of the 16th July, the day before the attack, my grandpa gathered his men to discuss the details of the action and check that they were all ready. The soldiers listened in tense silence, smoking and swearing under their breath. Then they tried to break the tension, joking with one another and passing around the few bottles of wine they had managed to get their hands on. My grandpa encouraged them to rest as much as possible that night, and then headed off to his tent, smiling in encouragement.

In the lonely darkness of his field tent, he wrote loving letters to Ginetta and his family, taking care not to let his hand shake as he did. Once again, he had to face a black wave of panic, which he felt rising from his stomach to his throat, threatening to paralyse him. He forced himself to take several deep breaths and when he had managed to relax enough, he fell into an exhausted sleep, the last words of prayer still on his lips.

The next morning, he managed to drink just a sip of water for breakfast and smoke a few cigarettes as he walked towards the initial assault position, followed by the other soldiers. The entire unit walked in silence and the only sound timidly filling the air was the rustle of footsteps on grass. Each man was plunged in his own fears, his mind twisting around the possibility of his imminent death. “Let’s get this done and hope it’s all over soon” my grandpa thought, angrily stamping out his last cigarette butt with his boot. After a few more steps he got on the ground, amid the grass and bushes, and crawled towards the starting position for the assault. To his right, he saw Mazzoni, his face squashed under his helmet, who nodded at him resolutely. They looked at one another in the eyes and in that look my grandpa found a new source of courage. If he had to die, at least he would not be alone.

“Courage, boys” he whispered, looking at his men lying in the grass around him, “advance quickly and stay far apart. They’ll be firing at groups of men. We’ll manage this, you’ll see.” Then he turned to look at the river, passing calmly, indifferently by just ahead of them, and waited for the preparatory artillery shelling to begin.

The first shots were fired at 6:40am. The roar of the canon fire was immediately followed by the piercing howl of the bullets flying over the bersaglieri’s heads, crossing to the other side of the river, raising columns of dust. My grandpa found himself watching that spectacle of destruction with joy, praying that it would cause as many German victims as possible.

A few minutes later, the enemy artillery woke up and returned fire, in an attempt to launch an effective counterbattery effort. Fortunately, the shots went long and did not hit my grandpa’s unit, which was crouching in the brush, by now impatient to leap forward.

The exchange of fire went on for 30 endless minutes. A wait that seemed to last a lifetime. Finally, at 7:10, the Italian artillery stopped firing, and the signal to attack was given.

Screaming at the top of his lungs, a scream of rage, desperation and a thirst for courage, my grandpa sprang forward, along with the rest of his unit, and ran towards the river. The other soldiers around him were shouting too, and the roar of hundreds of men charging all together made him feel both like crying and, at least for a second, invincible. It was a terrifying and beautiful sight, an irreconcilable, mad contradiction that an entire lifetime of reflection would struggle to understand and explain.

As soon as they reached the river and began to wade across it, however, the spell of those moments, balancing on a razor’s edge in time, was shattered. The Germans had prepared their defences well, and when the bersaglieri were within range they showered them with fire. The first to open fire were the automatic weapons lined up on the riverbank, immediately followed by the mortars in the rear. The deafening thunder of gunfire and explosions quickly obscured the battlefield, and my grandpa found himself moving forward on his stomach, his face in the mud and his fingers gripping the earth.

“Stay down!” he shouted at his men, with his remaining breath, looking around him. For some it was already too late. A few dozen metres to his left, he saw one of his soldiers explode in a red blur, when an enemy bullet hit one of the hand grenades hanging from his belt. There was nothing left of him, just a few fragments of his body scattered on the field.

I remember when he told me that story. He moved his hands up, miming the effect of the explosion. I remember watching him in amazement, motionless, incapable of imagining a whole man disappearing like that.

“Bastards!” he shouted as he began to fire. He trained his automatic Beretta on the dots of light of the enemy machine guns firing on him and began to empty one cartridge after another. But it was hopeless – the Germans were too well entrenched, the terrain behind the Musone river did not offer enough cover, and he and his men were easy targets in the clear morning light.

He tried to take a step forward to better take aim, but as soon as he got to his feet a mortar shell fell a few steps away from him. Before he knew what was happening, he found himself thrown off the ground by the blast, unable to breathe as the world turned on its head around him.

His eyes filled with dirt as his body traced a ragged arc through the air, unable to control or slow down his movement. He landed heavily on his back and rolled on the grass, over his gun, before coming to a stop a few metres away from his original position. From where he lay, he forced himself to breathe, even as he felt that the explosion had crushed his chest. A deafening buzz rang in his ears, drowning out all the other sounds of the conflict around him. The figures who were shooting and being shot at around him moved and died soundlessly, as if they existed in another dimension to which he did not belong.

He suddenly had the thought that he might be injured and would not have noticed. He touched his arms and legs frantically, his heart beating madly as if it would jump out of his chest, until he discovered that miraculously he had not been hit. The only visible damage was to the right strap of his pack, which had been sliced clean through by mortar shrapnel. A few millimetres lower or to the left and it would have gone into his ribcage or lodged in his head. He had survived by a hair’s breadth.

My grandpa told me this story many times, and it struck me because at some point I realised that that morning my life had been saved in that miracle, too. On one of those occasions, he was telling it to my classmates, in the last year of primary school. We had recently studied the second world war, and I had thought that perhaps my grandpa could share some of his incredible stories with the class. Luckily, both he and my teacher accepted this suggestion with good grace.

So it was that on a bright spring morning I found him sitting at the teacher’s desk in front of us, while with a shy smile he tried to paint a picture of what happened without alarming or scaring us. I looked at him with almost irrepressible pride, so much so that at times I forgot to listen to what he was saying. I must have been more excited than him, and at the end of the lesson I couldn’t help myself running over to hug him. “Thank you, grandpa!” I shouted, hugging his legs. He picked me up and gave me a loud kiss on the cheek. “It was fun” he said, with a smile that lit up the room. And perhaps he felt that by surviving that morning in ‘44 and that bloody war he had not just saved himself, but all of us children too.

In the end, the breaching of the Musone was only partially successful. My grandpa’s bersaglieri, having suffered too many losses, were forced to retreat. On the right, however, the 68th Infantry Regiment managed to cross the river and reach the village of Casenuove at 12:45, having cut a swathe using bayonets and hand grenades. Exhausted, they were eventually overtaken by the 9th Assault Unit, which continued the offensive and managed to enter the village of Rustico, to the north, by evening. My grandpa later saw the effects of those battles and told me of German soldiers, their skulls staved in by rifle butts, killed in a merciless clash. When he told me this, on one of the rare moments when the reality of war filtered through his memories, he closed his eyes and jerked his head as if to throw the memory far away. Then he turned to look at me and his eyes seemed to be asking for forgiveness. For what he had seen, perhaps. Or what he had done. Or what he had just told me. Or for all of those reasons.

On the night of the 17th July, having collected the injured and rested for a few hours, swallowing his tears, my grandpa and the other bersaglieri once more advanced towards the Musone river, this time under the cover of darkness, managing to gain a beach head on the other bank.

They spent the rest of the night in a state of febrile alert, because on the morning of the 18th there would be a new offensive launched across the whole line. The bersaglieri moved from their new positions on the Musone, attacking directly northwards, while the troops that had reached Rustico the previous day continued their advance, this time moving westwards. The various units of the CIL involved in the operation converged, in a pincer movement, on Santa Maria Nuova, just south of Jesi, where the lion’s share of the enemy artillery was positioned.

The battle to take the village raged all day, with mortar shells and machine gun fire raining down. The Germans brought the much feared 88 canons into the fray from the north of Jesi, furiously targeting the approaching Italian soldiers. At the end of the day, Santa Maria Nuova fell into the hands of the CIL, while at the same time the Polish contingent, in a perfectly coordinated action, was concluding the liberation of Ancona.

The bloody pushback against the Germans had worked. The battles, though, had been desperately violent, to the point that General Anders declared that in those days he had witnessed the cruellest fighting of the war, after Cassino. Crossing the Musone and capturing Santa Maria Nuova cost Utili’s contingent 79 lives and injured 121. From the beginning of the operations in Filottrano, the CIL had suffered losses of over 500 men in just 10 days of fighting.

I imagine that these were the scenes my grandpa had in mind when he told me that courage, in war, does not exist. There is just desperation and the will for it to all be over, in any way and at any cost. Sometimes the tension, the fear, the fatigue and the horror can break something within a man, and he can do things that he would have found unimaginable just moments earlier, even risking his life. Or actively seeking death. The line between courage and suicide is very thin, drawn in the sand and whipped at by the wind.

There were, however, several examples of bravery on the Musone. Most have been forgotten forever, lost in the mists of time. At least two, however, have been recorded.

The first involved Angelo De Sena, a soldier in the 68th Infantry Regiment, who died during one of the most furious assaults, and was posthumously awarded the gold medal for military valour: “During a tough battle against a well-armed German position, he spotted a machine gun that had killed three of his companions (…), attacked it with determination, killing two Germans (…). He went on to attack another position, with sang froid and precision. Injured on one side, he refused assistance, continuing to advance at an admirable pace. Having run out of ammunition, he threw himself on enemy positions using hand grenades. Fatally injured by a hail of machine gun bullets, he fell on the captured enemy position still clutching his last hand grenade.”

The second is that of Sergeant Giuseppe Ricciardi, who was working on supplies to the Nembo but was present, at his own request, in several dangerous operations. He was also awarded a posthumous gold medal for military valour with the following explanation: “On an incredibly difficult day, he volunteered for four different risky endeavours, finally fatally wounded while breaking cover, standing serenely, training his machine gun fire on targets that he had personally spotted and recognised.”

Ricciardi’s will was found in his bloody uniform, along with a message for his mother: “Don’t cry for me, mum, because I am not crying. I gave my all and I’m only sorry I didn’t do enough; it’s not my fault and that reassures me. Dearest mum, when you read these lines I will have gone to meet dad. I hope our sacrifice will serve the salvation of our children, and our Italy that I loved so dearly”.

To the Gothic Line

After the capture of Santa Maria Nuova, Jesi was within reach. The following day, the 19th July, after a quick meal and a few hours of rest, the bersaglieri of the 29th Battalion once again launched an assault, tracking the enemy in retreat. The advance was slowed down, however, by enemy fire, shooting at point blank range from their self-propelled guns, positioned at the eastern edge of the town. Worn out by the battle, during which even the haystacks in the fields were used for improvised cover, they were joined and overtaken by my grandpa and the bersaglieri of the 33rd Battalion, who continued the attack.

The day ended with the CIL almost ready to enter Jesi. Luckily, however, a battle for the town was unnecessary. At dawn on the 20th July, the patrols deployed by Utili realised that the Germans had abandoned Jesi during the night. The Piedmont Alpine Battalion could enter the town unopposed, liberating it without firing a single shot. Immediately afterwards, Utili moved his headquarters to the town.

Once Jesi had been occupied, the Poles were fairly confident that the Germans would not put up any further resistance before the Gothic Line. The advance therefore had to continue until it reached that system of fortifications, with the Poles on the coast and the Italians immediately to their left, slightly inland. The CIL’s next target was set as Ostra Vetere, beyond the Misa river.

Things didn’t work out exactly as planned. Utili ordered the San Marco Regiment to begin moving northwards, but the very next day, the 21st July, the Grado Battalion, which had just arrived at the line, was held off outside Jesi by violent German mortar and artillery fire, costing 22 lives and injuring 83. The 9th Assault Unit was called on to reinforce the advance, only to end up blocked on the road between Jesi and Acquasanta, provincial road 17. My grandpa and the 33rd Bersaglieri Battalion were thus sent back to the front, to reinforce the left flank. German defences had solidified unexpectedly, and the CIL, like the Poles, dug their heels in, expecting a German counterattack that intelligence had suggested was probable. But it never came – perhaps it was a mistake, or perhaps the Germans changed their mind.

After days of nervously smoking cigarettes and looking at the line, waiting for the German surge, on the 26th July the CIL patrols realised that the Germans had retreated. The advance was back on, with the 33rd Bersaglieri Battalion leading the way.

Blocking their route to Ostra Vetere was the Misa river, which flows into the Adriatica in Senigallia. On the 27th July, the 68th Infantry Regiment and the 33rd Bersaglieri Battalion were the first units to reach the river. The artillery, positioned behind them, was ready to fire if needed. The Germans had effectively slowed down the CIL’s movements for the whole day, with bombing raids, but without stopping them from getting to the river by sundown. Enemy fire was mostly aimed at the 68th Infantry Regiment, especially after they liberated the village of Vaccarile, just south of the Misa.

Once they reached the river, the Nembo Division was deployed on the left, the 1st Brigade, including my grandpa, in the centre, and the 2nd Brigade to the right. The Germans seemed solidly entrenched on the other side of the river and no one wanted to repeat the experience of the Musone. The front was static for an entire week, while the CIL joined forces with the partisans of the “Maiella band”, a group of apolitical republicans. The partisans, who throughout the winter had sabotaged German movements in the rearguard, were now protecting the left flank of the Italian contingent and from that position they rebuffed a German counterattack on the hills around the village of Montecarotto on the 29th July.

The Maiella Brigade, whose name was inspired by the Abruzzo mountain range of that name, was created in the autumn of 1943 and was the only partisan grouping that would be decorated with the gold medal for military valour on its flag, as well as one of few groups to be entirely incorporated into the allied army, taking part in several operations from Abruzzo right up to Veneto. Initially made up of around 500 partisans, its ranked swelled to reach 1,326 troops.

After a few days of deadlock exchanging artillery fire, on the 3rd August the Germans tried to breach the Italian line, attacking the left flank. The Nembo paratroopers were not caught off guard, however, and managed to rebuff the attack. Having failed in their operations, the enemies began to retreat, closely followed by the CIL. The following day, the San Marco Regiment, despite the losses it had suffered due to German rearguard activities, finally managed to capture Ostra Vetere, the initial target of the push north.

The Bafile Battalion of the San Marco Regiment included in its ranks Second Lieutenant Alfonso Casati, the illustrious son of Alessandro Casati, who was then Minister for War in the Bonomi government. The father, concerned for the fate of his only son, had found him a safe posting in Rome and tried to convince him to leave the CIL for a desk job out of harm’s way. On receiving that offer, Alfonso laughed and told him “Dad, I can’t defend the nation in Rome.” So he remained in his post, continuing to fight until a hail of machine gun bullets took him down during the fighting outside Ostra Vetere. The last time they met, he had told his father: “If something happens to me, you must continue your work as if I were alive.” And so it was: Alessandro Casati remained at the helm of the War Ministry in both Bonomi governments, later becoming, among other things, a senator for the Liberal Party, the president of the Supreme Defence Council and president of the Italian delegation to UNESCO. He now rests with his wife and son in the cemetery of Muggiò, in the province of Monza and Brianza.

At the end of hostilities, Alfonso Casati was awarded a posthumous gold medal for military valour. The explanation given states: “During a harsh battle he led his men in repeated attacks and counterattacks (…). In a subsequent action he volunteered to take part in a risky endeavour (…). During a break in the attack, brought about by the intense defence fire, he did not hesitate to go with a small group of brave men into controlled territory, which was open to enemy attention (…). Although aware of the deadly German reaction and conscious of the inevitable sacrifice (…) he continued his own effective action, inflicting remarkable losses on the adversary, while the action was crowned with success. Fatally wounded, he continued to encourage his men in battle with words and gestures”.

The Italian and Polish advance, once at Ostra Vetere, could not stop. On the 9th August the Poles took Cesano on the Adriatic coast north of Senigallia. In parallel, the CIL advanced and the next day reached the same line, capturing from left to right, Loretello, Castellone di Suasa and Corinaldo.

On that line, the Germans attempted to launch two counterattacks on the 11th and 13th of August. Just as in previous battles, then too the fighting was at close quarters, with soldiers in hand-to-hand combat and using grenades, while the opposing artillery engaged in long duels. Even so, the Italian line would not give. My grandpa didn’t know it yet, but this was the last fighting he would witness.

Having pushed back the attack, the CIL was moved inland by the Poles, between Gubbio and Sassoferrato, where Utili established his new headquarters. Two months after leaving the Mainarde, the Italian contingent was back in the mountains.

The main objective in this new area of operations was to take the town of Cagli, a necessary stage on the Via Flaminia between Rome and Fano, which is to say the Gothic Line. The Allies hoped that they could surprise the 5th German Mountain Division, which controlled the sector and had already faced off against the CIL on Monte Marrone and Monte Mare. The division had also fought around Leningrad, and in Italy would finish the war surrendering to the Americans near Turin.

The bersaglieri in my grandpa’s division were positioned, along with the rest of the 1st Brigade, on the left of the new front, between Scheggia and Cantiano, straddling the border between the regions of Umbria and Marche. The 2nd Brigade was positioned to the right, while the Nembo was in reserve. Everything was in place for what seemed to be another inevitable attack.

Retreat from the front

Luckily, however, on the 17th August Utili received orders from the Allies to withdraw the CIL from the frontline for a period of rest and reorganisation in the rear. After seven months spent on the line and having faced some of the toughest battles of the Italian campaign, on the Gustav line and at the Musone, the men were indeed exhausted, with dirty, patched up uniforms, boots worn through from hundreds of kilometres of marching, canons in poor condition after firing thousands of rounds, half of the vehicles destroyed by enemy fire and the other half in dire need of repair, which was impossible given the lack of spare parts. Not to mention that by then the Italian contingent had recorded 1,840 losses in total, between the dead, injured and missing, which was almost 10% of their manpower in August 1944. Given, however, that CIL numbers had swelled over the months and that it included the engineer corps, divisional services and the men of the headquarters, it was entirely possible that the losses suffered by the combat units, like my grandpa’s, well exceeded that figure of 10%. Bear in mind that with losses between 20 and 30% a military unit de facto loses its offensive capacities and can only be effective in defensive operations.

In August 1944, then, the CIL had effectively exhausted its forces and its energy. Keeping it on active duty for a longer period would have meant throwing it to the lions, and the Allies had enough good sense and good grace to withdraw them instead.

The operation to withdraw from the front was immediate but gradual, so as not to leave it unmanned from one day to the next. My grandpa and his men were among the first to leave, reaching the designated rest area in the outskirts of Macerata. The last to leave were the men of the San Marco Regiment, the Monte Granero Alpine Battalion, the 9th Assault Unit and a few artillery units. The San Marco and the 9th Assault Unit were pushed forward before their retreat, and they occupied, not without conflict, Cagli and Acqualagna to the north, which was liberated on the 23rd August.

On the 25th August the CIL again left the Polish corps and was once again brought under the orders of the 5th British Army Corps. General Anders once again wrote some parting words to Utili: “Here ends, to my great dismay, the bond of tactical and administrative organisation that tied the Polish Corps and the Italian Corps (…). I am unable to bid you farewell in person. I hope that my visit can be paid in the near future, when I will express my great appreciation for the part played by the CIL (…). Much Polish blood has been spilled on the soil of your great country; it was spilled in the name of the noble ideals of a civilisation that is our shared heritage. Please accept, along with my wishes, the wishes of the troops under my orders, to the Italian people and in particular to your Corps”. After the war, Anders moved to London, where he contributed to setting up and running the Polish government in exile, rivalling that put in place by the Soviets when the Cold War began. He died there in 1970, at the age of 77. In line with his wishes, he was buried in Italy in the Polish military cemetery in Montecassino, alongside his men.

After the handover from the Polish to the British, the last CIL units still at the front made one last push forward, and on the 29th August entered Urbania and on the 30th, Peglio. By then, the Gothic Line had been reached and the entire allied advance came to a halt. The last Italian soldiers on the front were then evacuated and reunited with their comrades who had already been withdrawn.

One of those evenings in Macerata, my grandpa looked around and his eyes came to rest on his exhausted men, among the other CIL soldiers moving around him. They wore a stunned expression and walked slowly, stepping cautiously, as if the return to a life without violence was a kind of spell that could be broken by a sudden movement. He looked down at himself and saw his hands, finally freed from bearing arms. He ran them over his face and through his hair, feeling a tear streaking down his cheek like a single drop of rain. He had done it: he was still alive. He looked up and filled his eyes with sky, breathing in the sweet evening air until he felt like his lungs would explode. Finally, a smile spread across his face for the first time in a long time.

For him, the war was over.