Translated into English by Aimee Van Vliet

Dissolving the CIL

Upon their arrival at the meeting point south of Macerata, the Italian soldiers were met with the news that the CIL was being disbanded.

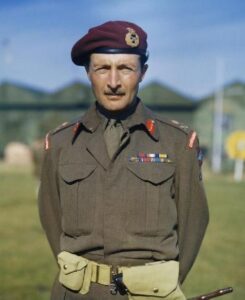

General Browning, the head of the Allied Forces Control Subcommittee, paid them a visit in person on the 30th August 1944 and informed them of the decision with the following words: “The Italian army has been a great help to the allied cause (…). The CIL fought well and suffered losses (…). I am delighted to inform you that General Alexander has requested British material to rearm and reequip large sections of the Italian army. We are currently preparing the Friuli and Cremona divisions (…). You have been of great service to Italy. If you had not fought well, General Alexander would not have asked allied governments to form a larger Italian combat force. That is a great satisfaction for you and for Italy”.

Many soldiers held their breath as he began his speech, hoping that Browning might be about to tell them that their time bearing arms was over, and that they would soon be heading home. But it was not to be.

The Allies had indeed decided to expand the Italian contingent, rearm it and resupply it with entirely British equipment, and to organise it into completely new divisions, called Combat Groups. Those units would come under the American or British Army Corps and continue to fight, at a moment when operations on the western front were forcing the Allies to move increasing numbers of units from Italy to France.

When Browning spoke to the men of CIL, he made efforts to be flattering and diplomatic. But it escaped no one’s attention that under the restructuring plan, the Combat Groups would be subsumed into allied armies, with no identifiably Italian force present on the front line. The Italians would no longer fight together, and their successes would no longer be purely theirs. My grandpa and the other soldiers looked at one another in silence, their initial hope and satisfaction giving rise to bitterness. In spite of all the difficulties they had encountered over those months, the CIL had become their home and the thought of leaving it, of abandoning the people with whom they had shared months of suffering felt like ripping a bunch of grass from the ground and scattering it to the wind.

During that period of limbo, Utili stayed with his men, trying to encourage them. He walked among them, squeezing their shoulders and touching their faces, trying to explain that the allied decision was purely needs based, and should not be interpreted as a punishment or as a show of indifference. But he was not given much time.

The CIL was officially scheduled to disband on the 25th September. The day before, Utili decided to permanently take leave of his men. He chose these words in doing so: “The CIL is being disbanded for reasons beyond my powers. What cannot be disbanded, and I don’t believe will ever fade, is the shared heritage of noble, difficult feats that we have lived through together (…). I am certain that everyone who has belonged to the CIL will recognise each other as brothers and will always hold out our hand to one another, whatever the material or spiritual fate dealt to each of us on our individual paths”. It was a moving farewell. On hearing it, everyone felt that not even war would protect them from the harsh demands of life, managing as it did to fling them onto different paths.

In the same month, the morale of the Italian contingent was further shattered by another event. Fucci, an official who had become legendary, who had been a commander of the bersaglieri since Corsica and was more recently at the head of the first CIL brigade, was driving behind the lines in his jeep when he hit a German landmine. Keeping his distance from the front line had clearly not been enough to protect him.

The explosion was enormous, and Fucci was dragged from the wreckage with serious injuries. After a long battle, he somehow survived, hanging onto life by tooth and nail, but he lost both legs and any chance of contributing to the final months of the war. To everyone’s great regret, including Utili, he was told he would be hospitalised for around a year, which meant that he would only be discharged once hostilities had ceased.

Fucci stayed in the army for the rest of his life, and retired with the rank of Lieutenant General, then in 1960 was awarded the title of High Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic. After his death, in Naples in 1980, his hometown of Barletta produced a memorial plaque that was placed in the gardens of the Swabian castle there.

A similar fate met Kesselring the following month, when he came close to losing his life after his car crashed into a self-propelled artillery. He was evacuated and admitted to several months of care, and only rejoined active service in March 1945, when Hitler named him commander-in-chief of the western front, in a desperate attempt to contain the rampant allied offensive. The man who for months had made Italy a death trap for the Allies was eventually taken out of commission by a simple traffic accident.

When the CIL was eventually dissolved, the Italian soldiers began to leave Macerata to be reassigned to the future Combat Groups. My grandfather and the bersaglieri of the 4th Regiment were transferred first to Assisi, then were put on a train to Vairano in the province of Caserta. From there, they travelled in covered trucks to Piedimonte d’Alife, also in the province of Caserta, where they stopped to await further orders.

While they were being transferred, General Messe, the chief of staff of the Italian cobelligerent army, was informed of the Allies’ plans as they looked beyond the liberation of Italy. The plan was to create twelve Combat Groups, first deployed to fight Germany, then Japan, to force the last holdouts of the Axis into unconditional surrender. The massacre unleashed by the two American atom bombs would put paid to that intention, which would have forced Italians and other allied forces to invade Japan by sea, in comparison to which the Normandy landings would have seemed like small fry. The blood tribute necessary to put a definitive end to the war’s orgy of madness was paid by 200,000 Japanese civilians. More people died in the two blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki than were lost by the Germans and Allies in five months of furious fighting on the Gustav line and around Anzio.

Operations on the Gothic Line

While the Italian contingent was being reassigned to its new units, the Allies began taking on the Gothic Line.

At that stage in the war, the British and Americans had a clear numerical advantage over the Germans and were enjoying an almost unchallenged domination of the skies. Their bombers had destroyed the road network of northern Italy so effectively that Hitler would have been unable to effectively supply his units or withdraw them from the front line even if he wanted to. The German rear guard was swarming with an army of around 80,000 Italian partisans that regularly disrupted their operations.

In spite of all this, the German army gave no sign of wanting to surrender. The allied offensive on the Gothic Line was launched as soon as they reached it, in August 1944, in the hope that the final weeks of summer would be enough for them to break through it and claim victory once and for all. The British flung themselves at enemy defences on the Adriatic coast, while the Americans began a tough advance across the central section of the Apennines. The Germans staggered under the violent allied strike and were eventually forced to abandon their bunkers and trenches. Even so, they managed to avoid defeat.

Although they had made it past the Gothic Line, the Allies were not fast enough to reach the Po valley before winter arrived. Adverse weather conditions, along with the enemy’s strenuous resistance held them to mountain positions, where in October they were forced to throw in the towel. Although they had the plains in their sights, they had to resign themselves to spending another long winter waiting in that inhospitable terrain, preparing for what would be the final offensive in April 1945.

When operations on the front stalled and subsided, General Alexander, the commander of all allied forces in Italy, went on air at the ‘Italy at War’ radio station, used by the British and American command to contact CLN groups, and made an announcement that was destined to go down in history.

In the late afternoon of the 13th November, he addressed the partisans working behind enemy lines and asked them to cease their large-scale activities and withdraw to defensive positions, announcing that the Allies would do the same for the winter. That day, several representatives of the resistance listened, dumbstruck, to the words “Patriots! The summer campaign (…) is over: now the winter campaign has begun (…). The rain and the mud cannot fail to slow down the allied advance, and patriots must stop their activities in order to prepare for a new stage in the fight and face a new enemy, winter. This will be very hard for patriots, due to the difficulties in supplies of food and equipment; there will be few nights when it will be possible to fly in the coming months, and that will limit our opportunities to make airdrops”. Alexander went on to say that it was by now necessary “to hold on to munitions and materials and stand by for further orders”, even if it was still possible to “take advantage of favourable opportunities to attack the Germans and fascists”.

That message, which became known in the history books as the Alexander Proclamation, managed the difficult task of coming across as both misguided in its contents, because it was easy for the enemy to intercept and thus to anticipate the Allies’ intentions for the coming months, and imperious in tone. Those who wished to continue fighting, such as Luigi Longo, the Deputy Commander of the Voluntary Liberation Corps, threw up his hands, fearing that Italian soldiers would interpret his words as an invitation to give up and go home. Which was in part what happened, as estimates of active partisans fell from 80,000 to around 50,000 at the end of 1944. This was all made easier by the fact that the Germans, who were sure that the Allies would not attack again until the spring, felt free to concentrate almost entirely on crushing the resistance, launching a number of raids across the entire territory still under their control. It was a hard winter, which forced many partisans to scatter across the plains of the Po valley, damaging not only their numerical ranks but also the insurgency strategy that they had been working on for so long.

However, given the consequences of his broadcast, it seems likely that Alexander had no intention of causing such damage, and that he was simply misrepresented. In a letter that he wrote at the time to his direct superior, Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, the Supreme Allied Commander of the Mediterranean, he had indeed written: “I feel very strongly that everything possible should be done to increase supply airdrops to Italian partisans, so that they can make massive efforts, in collaboration with my offensive operations”.

His was probably a clumsy attempt to coordinate allied activities with those of the partisans, or at least not to create false hopes of imminent liberation among the population of northern Italy. It remains surprising, however, that a commander of his standing and experience could have stumbled into such a basic error in communication at such a critical moment.

In any case, Alexander’s days at the head of the allied army in Italy were numbered. In January of 1945 he was appointed as the commander of the entire Mediterranean theatre and was replaced by General Clark, who took over the running of the troops stationed in the Apennines and had the task of making the final push against the German army.

A few days later, in February, Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill met in Yalta. It was a very different meeting to the one held in Tehran in in November 1943. At that time, Stalin had seemed destined to play a supporting role. But this time, with the Red Army on its way to Berlin, and the United Kingdom exhausted after years of war, it was Churchill who was on the sidelines. During the meeting, the leaders discussed the post-war map of Europe in detail, as well as approving the plan to set up the UN, which Roosevelt strongly supported. They also established that when hostilities ended all countries involved would hold free elections. Churchill understood, but was powerless to avoid it, that Stalin would not honour his commitment.

After Yalta, then, Europe seemed doomed to the long confrontation of the Cold War. If Roosevelt had intervened, he could potentially have swayed the dynamic of the meeting and changed the course of history. But by that point the American president, a long-time smoker, had been sick for some time, and had neither the strength, the vision or the desire to use his last energy to stand up to Stalin. In the photos of him from that time, he seems to be drowning in the clothes he is wearing, as his hollowed-out body slowly disappears into the folds. He died of a stroke a few weeks later, on the 12th April 1945, and would not see the end of the war or the triumph of the Allies.

The final offensive

The British and Americans’ final assault on German lines in Italy was originally scheduled for the 9th April 1945. The main objective was to overwhelm the enemy before it could retreat to the other bank of the Po, beyond which no other defensive lines could be established before the Alps.

Poor weather conditions meant that the offensive was put back to the 14th April. When it was finally launched, the Germans held out for three days, in spite of their by then desperate conditions. The final breakthrough only took place on the 17th April, when the Allies managed to reach via Emilia, a straight line cutting across the Po valley between Milan and Rimini. With that accomplished, the capture of Bologna became inevitable.

At the time operations were launched, only six of the twelve Combat Groups had been formed: Legnano, Cremona, Friuli, Folgore, Piceno and Mantova, although the latter was not formed in time to join the fighting. Uniforms, helmets, vehicles and weapons were all British, with all Italian soldiers having been trained to use them in the previous months, in training programmes lasting between 12 and 17 weeks. The only feature that distinguished the Italians from the British soldiers at that point were the badges of their corps on their jacket lapels and a small Italian flag sewn on their left sleeve.

Soldiers who had fought with the CIL were not the only Italians in the Combat Groups. Thousands of volunteers had turned up during those days to swell their ranks and contribute to the Allies’ final push. Many of them were demobilised soldiers from the Royal Army, or partisans. It had been clear for several months which side most Italians wanted to fight with as the war came to an end.

Of all Combat Groups, Legnano was the first to see action. Led by General Utili, it was made up of various CIL divisions: the IX Assault Division, the 68th Infantry Regiment and other bersaglieri and Alpine units. It was sent to the front line in the central Apennines at the end of March 1945, when the April offensive was launched, heading straight for Bologna, which they liberated in triumph on the 21st. Taking the city was Utili’s greatest moment and he treasured it for the rest of his life.

The Legnano continued its advance, reaching Brescia on the 29th, Bergamo on the 30th and Turin on the 2nd May, when hostilities officially ceased. In all, they recorded 55 deaths and 279 injured.

Utili survived the battles and stayed in in the army after the war. He died of a heart attack in 1952 at the age of 57. His final resting place was the Italian military cemetery in Mignano Monte Lungo, alongside the hundreds of soldiers who were once his men. Commenting on the deprivation they had suffered during the war of liberation, and the limited acknowledgement they had received during and after the hostilities, Utili declared: “I have never seen any other soldiers resigned to going to war in those conditions, with people so neglectful and indifferent to their suffering behind them”.

The Friuli Combat Group was the successor to the Friuli Division that had stood out during the battles in Corsica in which my grandpa was involved. It was sent to the front in February 1945, to the area of Brisighella in the province of Ravenna, where it immediately repelled a German counterattack. During the April offensive it advanced along the via Emilia and liberated Bologna, alongside the Legnano. It recorded 242 deaths, 657 injured and 61 missing.

Folgore was made up of the Nembo Division and the San Marco Regiment of the CIL. It reached the front in March 1945 and was used to hasten Friuli’s advance to Bologna. It recorded 164 deaths, 244 injured and 14 missing.

Cremona, like Friuli, was the reorganisation of the division of the same name that had fought in Corsica and, unusually, included the entire “Mario Gordini” partisan brigade, which had communist leanings. General Zanussi, the commander of the Cremona infantry, summarised the relationship between the partisans and soldiers in his ranks as follows: “While they were fighting, fine, out of it, bad”. Luckily, divergent political opinions did not distract them from their ultimate goal, and fighting the nazi-fascist armies remained the top priority for everyone.

As soon as it was assembled, Cremona was integrated into the Canadian Corps and sent to the front in January 1945. Deployed between the Adriatic coast and Alfonsine in the province of Ravenna, it held off several German counterattacks and in March began to move towards the Comacchio marshes. Later, it was given the order to head directly north, aiming for Ariano nel Polesine, where my grandpa was born, while the 56th British division advanced up the Ferrara-Rovigo-Padua line on its left flank. Polesine, the birthplace of Matteotti, had suffered from squad violence since the early days of fascism, and would bear the yoke of war and occupation right to the bitter end of the fighting.

Facing off against Cremona were elements of the ‘Turkmenistan’ 162nd German infantry division, and a brigade of Italian fascists. The 162nd was made up almost entirely of soldiers from the Caucasus and Turkmenistan, recruited from the German army’s prisoners of war and Red Army deserters. The German army was evaporating by this point. At the end of hostilities, the survivors of the 162nd turned themselves in to the Allies close to Padua. Quickly delivered to the Soviet Union, they were almost all sentenced to several years’ hard labour in the Siberian gulags for having fought with the enemy.

When Cremona began its offensive in Polesine, it managed to get in via a bridge over the Po in Goro that the retreating enemy had not entirely destroyed. Once they were on the other side, however, they were targeted by machine gun and artillery fire, including the terrifying German 88 cannons. Ariano was captured, not without difficulty, between the 23rd and the 24th April, after clashes that cost Cremona 2 dead and 8 injured.

When the Allies began to flood into the Polesine, the Germans wanted to carry out one last reprisal before retreating for good. On the 25th April they lined up twenty partisans, captured in Ceregnano in the Palà district, against the cemetery wall in Villadose where a firing squad mowed them down. Once they had completed the executions, they also shot the two Italian fascists who had assisted them. Political colours mattered little by this point: the only important thing was to kill a few more Italians before the final ceasefire prevented it once and for all.

In the meantime, Cremona had managed to cross the Po in part thanks to temporary bridges built with the help of the local population. Adria and Loreo were easily reached on the 25th April, while Cavarzere, a village on the Adige river, was the theatre of one of the last bloody battles of the war. The enemy had barricaded itself in with machine guns, mortars and light cannons, drawing Cremona into what would become a desperate, house to house fight. The British Air Force was called in to do away with that last desperate defensive bastion, which fell after being reduced to rubble on the evening of the 27th April.

Once it had overcome that obstacle, the Cremona met no further resistance. It entered Chioggia on the 29th April, and the enemy forces who had stopped there were made prisoners and forced to use their boats and tugs to ferry Italian troops over the Brenta river. In the evening of the same day, Cremona entered Venice, where an Italian flag was raised in Piazza San Marco, the population pouring into the streets to celebrate a long-awaited victory. By the time it reached the end of its tour of operations, the Cremona had recorded 178 dead, 605 injured and 80 missing.

Luckily, my grandpa was assigned to the Piceno Combat Group, which was not deployed on the front line. The reason he was spared the requirement to fight until the end has been lost in time. Perhaps it was a coincidence, or perhaps it was a carefully considered decision taken by someone higher up, who realised that my grandpa had already spent long enough on the front line over the course of the two previous years.

The decision to send him to the rear must have pleased him, even though it meant saying goodbye to Mazzoni, who he had known for three years and who had supported him after Borghi’s death. When the time came for them to take their leave, they stood looking at each other for a while in silence, unable to find anything meaningful to say. They had meant too much to each other, so they say a hasty goodbye, squeezing each other’s shoulders and looking each other in the eye with a hint of a smile on their lips, before turning to face their fate for the last few months of the war. They would not see each other again.

The Piceno Combat Group was officially formed on the 10th October 1944, from the Piceno Division of the Italian army, which had defended Brindisi and was later involved in security and surveillance activities. Initially, the Combat Group provided troops for logistical and public order missions, but in January 1945, when it became clear that they would not be sent to the front line, it became a ‘training camp for Italian combat troops’.

My grandpa was assigned to the Piceno group on the 27th October 1944. At the time, the Combat Group was stationed in Taranto, but after it was turned into a training camp it was transferred to Cesano, close to Lake Bracciano in the region of Rome, where the Italian army’s infantry school is still based. My grandpa reached his new quarters on the 8th January 1945 and stayed until the 16th June, when the war was already over, and he was sent on pre-demob leave. His last few weeks in the army were spent training the soldiers who would contribute to the final push against the Germans.

Knowing my grandpa’s character, I can imagine that new recruits wished for any instructor but him. Still I like to think that, thanks to his firmness, some of the soldiers may have learned a little more and got home alive as a result. It also seems unlikely that he would have tried to befriend the younger men. They were all inevitably leaving for the front, and I don’t think he wanted to risk any more grief. All he must have wanted at that point was to be left in peace.

He was finally discharged on the 3rd July 1945, almost four years exactly after he had first left for the officers’ school in Pola and his odyssey had begun. Leaving his base camp in Cesano, he cast a backward glance and ran his gaze over the streets crowded with men in uniform, the sandbags piled up at the entrance and the dusty barracks that had housed him and many other young men over the months. For a moment, he tried to remember the man he had been before the war, but he struggled to recognise himself. His memories of those days seemed to be someone else’s, someone who had lived a long time before, in another world. Ultimately it was of no importance, he thought, as he lifted his pack onto his back and set off. The only thing that mattered now was that Ginetta was waiting for him in Altopascio. And he had to find a way to reach her as soon as he could.

The end of a world

While my grandpa spent his last few weeks in the army, the world he had known was falling apart, one piece at a time.

Overwhelmed by the allied offensive in April, many German soldiers had tried to escape by swimming across the Po river. But they were not given a moment’s respite. On the 25th April, partisan forces, weakened as they had been by General Alexander’s announcement, launched a general insurrection, attacking the enemy as they fled. The next day, the Americans entered Verona, while the Adige river was crossed on the 27th.

Faced with this unstoppable defeat, General Wolff, who was the head of the SS in Italy, and General Vietinghoff, who along with von Senger und Etterlin had replaced Kesselring at the head of the Wehrmacht on the Italian front, decided to ignore Hitler’s orders to resist until the last man, and prepared to sign an unconditional surrender.

Behind the scenes, negotiations to do so had already begun in February and would probably have contributed to an earlier end to the war in Italy had Himmler, head of the SS and number two in the Nazi regime, not suspended them one month in. In spite of his interference, however, plenipotentiaries appointed by Wolff and Vietinghoff still managed to meet with the Allies at the royal palace in Caserta, their headquarters in Italy, to sign their surrender on 29th April. The document decreed that the ceasefire would begin at 2pm on the 2nd May.

By the time the German army laid down its weapons, Mussolini was already dead.

A few days earlier, Il Duce, gripped by panic, had tried to escape to Switzerland, but the Swiss trade advisor in Milan told him that Italian politicians arriving at the Swiss border would only be let through following the deliberations of the federal department. With the Allies running rampant and unlikely to wait for the proper Swiss administrative processes to run their course, this response was tantamount to refusal.

With that door closed to him, Mussolini became almost entirely incapable of eating or sleeping. He left Salò on the 18th April and transferred what was left of his government to Milan, the city where it had all begun and where the first combat fascio had been founded. He was accompanied by Claretta Petacci, the woman 29 years younger than him who had been his lover since 1932. Although she knew that staying by Mussolini’s side would be dangerous, she justified her choice to her sister, saying: “I am following my destiny, which is his. I will never abandon him, whatever happens”.

In the clutches of growing panic, Il Duce imagined that he could use the church to negotiate his surrender. On the 25th April, with the partisan uprising exploding around him, he met with the Archbishop of Milan, Idelfonso Schuster, who had organised a meeting with representatives of the CNL. Shortly before meeting with them, Mussolini confided in the clergyman that he wished to retire to Valtellina, with a group of 3,000 loyalists, to hold on for a few more hours or days before giving himself up. After an embarrassed silence, the Archbishop pointed out to him that his was an impossible proposal, and that at that point he would be hard pressed to find even three hundred supporters ready to fight for him. “I may get more than that, but only a few more”, Mussolini replied with a sad smile. “I am under no illusion”.

When they arrived, the CLN delegates explained that they had not come to negotiate. They had one very simple request, and that was that Mussolini, the Fascists and the Germans surrender immediately and without conditions. Mussolini squirmed and took his time, fearing that the partisans’ only aim was to imprison and execute him. He wasn’t far off.

On the evening of the 25th he fled Milan and reached Como with his entourage, to whom he brandished a revolver and said “I’ll take care of myself”. Perhaps he was just trying to summon his courage.

Unable to take a decision about what to do, he began to wander about, until, in the night of the 26th to the 27th, he ran into a retreating German anti-aircraft unit heading for South Tyrol. He decided that he would throw himself on their mercy, and to avoid being recognised he put on a corporal’s jacket and a Wehrmacht helmet.

His disguise was not enough. The column was intercepted on the 27th, close to the town of Musso on Lake Como, by a roadblock set up by the partisans of the 52nd Garibaldi “Luigi Clerici” brigade, headed by Pier Luigi Bellini delle Stelle. During their inspection they recognised Mussolini’s unmistakeable features and Il Duce was taken prisoner along with his entourage, while the Germans were allowed to continue on their way.

Having been captured by the partisans, Mussolini and Petacci were transferred between several locations, to avoid them falling into allied hands. The command of the Northern Italy National Liberation Committee (CLNAI), based in Milan and led by Luigi Longo, Emilio Sereni, Sandro Pertini and Leo Valiani, had indeed decided that in the event of capture Mussolini should be shot. Handing him over to the Allies would be tantamount to putting twenty years of Italian political life on trial, and therefore the entire Italian population, given that separating the dictator’s responsibilities from the nation’s would be an almost impossible task, as well as painful and embarrassing. It was better to get it over with immediately, as quickly and discreetly as possible.

That night, Mussolini and Petacci were kept in a farmhouse in Giulino di Mezzegra, in the province of Como. It was the first night that they had ever spent together, in spite of having been lovers for thirteen years. For that entire time, Claretta had lived on the crumbs of affection that Il Duce would throw her, silently resigned to not being the only woman in his bed. But on that final, desperate night, they were all that was left of the world to each other. Perhaps they spoke to each other with a sincerity that circumstances and priorities had always made impossible or found the strength to share a final moment of intimacy. Or perhaps they cried in each other’s arms, crushed by remorse for missed opportunities and the indelible legacy of horror they left behind them.

The next day, on the 28th April, two partisans, Walter Audisio and Aldo Lampredi, were sent to finish the job. They set off at dawn, and as they arrived Audisio gave orders to shoot all prisoners immediately, with a determination and haste that appeared cold-blooded even to the other partisans present. Pier Luigi Bellini delle Stelle tried to intervene at least on Petacci’s behalf, exclaiming “She’s not guilty of anything!”. But Adusio replied that she had been ‘Mussolini’s advisor, inspiring his policies for years. She is as responsible as he is”. That version was later discredited by both Valiani and Pertini: the CLNAI had never ordered that Claretta should be shot.

Whether or not the order was given was no longer important. Mussolini and Petacci were put against a wall, together, and shot without ceremony. The other commanders arrested with them met the same fate.

History has never established who exactly executed Il Duce. Perhaps it was Audisio himself, or perhaps it was another of the partisans present. Some even claimed that it was Luigi Longo, that he travelled to where Mussolini was imprisoned to finish him off himself. After all these years, the mystery is still intact, and will probably never be solved.

After the executions, Audisio had the idea to load the executed bodies onto a truck, take them to Milan and leave them in Piazzale Loreto, where 15 partisans had once been shot and displayed in public for an entire day, covered in blood and flies. Having unloaded them at the chosen spot, some of the bodies were hung upside down, including Mussolini and Petacci, and fed to the crowd, who gathered around them to celebrate, insulting and tarnishing them. It was a chaotic but inevitable reaction, after so many years of war and violence. Indeed, it was the only the beginning of the score settling that would follow. It is estimated that in that period around 15,000 representatives of the regime were arrested and summarily executed throughout northern Italy. These vendettas were carried out with the tacit consent of the Allies, who decided to let the population unleash their fury, as long as it did not interfere with military operations.

Two days later, on the 30th April, with Red Army soldiers only two blocks away from his bunker, Hitler committed suicide, shooting himself in the head, while his wife Eva Braun did the same with a cyanide pill. Their bodies were dragged out of their hiding place and burned in an artillery crater, with the thunder of Soviet cannons still roaring around them. Berlin finally surrendered on the 2nd May, the same day that the ceasefire came into force in Italy, while Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender was accepted by the Allies on the 8th May.

The war in Europe and the bloody experiment of the Nazi-fascist regimes were over.

The last plank of the world my grandpa had grown up in, the Italian monarchy, collapsed around a year later.

On the 9th May 1946, in a desperate attempt to survive an institutional referendum called for the 2nd June, King Victor Emmanuel III permanently abdicated, passing the crown to his son, Umberto II, who had been the Lieutenant of the Kingdom since June 1944. The same evening, he boarded a ship to Alexandria in Egypt, where he withdrew in voluntary exile.

Umberto II followed suit on the 13th June, after the Italians voted for a republic. The Vatican had been strangely silent during the referendum campaign, and rumours immediately swirled that it was due to the new King possibly being bisexual. In any case, once he realised that the monarchy was defeated and that the Allies would not intervene to protect him in the event of an attack, Umberto II took a plane from Ciampino airport to Portugal, where he lived first in Colares, then in Cascais, both near Lisbon.

When the republican constitution came into force, on the 1st January 1948, his exile took on a permanent, legally binding character. His bitterness was reported in several interviews, Umberto reiterating that his departure “had been intended as a sabbatical to wait for tempers to cool” and that he had planned to return to “aid in the work of peacebuilding and reconstruction” and that “there had never been any mention of exile (…). Nor had I, at least, ever considered it”.

The history of Italy, though, no longer had space for him. He separated from his wife shortly after his arrival in Portugal and spent the last years of his life fighting a tumour that eventually killed him in 1983. He died alone, in a clinic in Geneva, holding a nurse’s hand.

His father had died shortly before Christmas 1947, of pulmonary edema. A few days earlier, on the 23rd December, he noticed that the post he received from Italy was lacking the Christmas greetings he still expected to receive in homage from many eminent figures. Looking at his adjutant, he hissed bitterly: “What a miserable world we live in”.

The Italian campaign

The war of liberation lasted 608 days and cost the Allies around 312,000 men, between the dead and injured, and 500,000 Germans, although estimates vary. That meant an average of around 1,335 soldiers taken out every day, not to mention civilian victims. During the final weeks of the campaign, the number of German soldiers aged 17 or 18 killed at the front shot up. The Reich was on its knees by that point and had started to use its youngest as cannon fodder.

The Italian war was one of attrition, fought on challenging terrain that prevented the broad, quick movements of tanks seen in Russia, France or Africa. The German defensive lines were often only breached after incessant artillery bombing and furious hand to hand combat, using techniques that seemed to belong more to the First World War than the second. In that context, a mere movement of supplies, over muddy mountain roads that had been pounded by artillery, was a huge logistical headache, requiring thousands of Italians to be employed as engineers, logistics, transport and security workers. The numbers working in those auxiliary units grew from approximately 60,000 men in October 1943 to over 196,000 in April 1945. An entire army, performing an essential role that was often overlooked by history books.

Ernie Pyle, an American journalist who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1944 for his war reporting, and was killed the following year on a small island off Okinawa, called those who fought in Italy “tough people, with guts”. And wrote this of his time spent on the peninsula: “Few of us have any good memories of the Italian campaign. The enemy was cruel, as were the elements. Anyone suffering received scant comfort – and there was none for those who died – from trying to understand why things happened the way they did”.

Moreover, the many deaths on both sides continued to haunt the survivors for the rest of their lives. General von Senger und Etterlin, whose troops my grandpa faced in Corsica and Italy, later confessed that “it was impossible ever to really forget” the war. And an American veteran, reflecting on his inability to leave the past behind him, wrote in his diary: “I must follow their spirits into purgatory, because I am strangely bound to everything that happened to them”. I think that my grandpa felt like they did for his whole life.

Much has been said, and written, on the usefulness and need for the Italian campaign. For some it was nothing more than a huge strategic blunder, in which thousands of lives were sacrificed to open a route that would never have allowed the Allies to get any further than the Alps. For the British and Americans, there was only ever one route to Berlin, and it necessarily started from an invasion of France.

There is certainly some truth in that analysis, but it is a partial judgement.

Without the experience gained from the landings in Salerno and Anzio, as Kesselring himself acknowledged, the crucial invasion of Normandy would have ended in a disastrous fiasco. Italy was indeed an essential test case to refine the Allies’ amphibious operations, which could ill afford to be pushed back to sea when they launched their attack on the Atlantic Wall. Not to mention that if fighting in Italy hadn’t diverted German soldiers, resources and energy, the allied advances towards Germany would have met with much greater resistance.

Moreover, it was thanks precisely to the allied conquest of Italy that they were able to push the German Navy out of the Mediterranean, opening a new route to send supplies to Stalin and capturing the airports they needed to bomb Germany and its infrastructure intensely.

Lastly, quite simply there was not an ocean-going fleet large enough to transport the huge allied contingent from the Mediterranean to Britain immediately after the end of fighting in Africa. The invasion of Italy was, beyond its strategic significance, an undeniable operational necessity for the Allies, especially considering that Stalin would not have allowed the British and Americans to stand idly by without engaging the Germans while the Soviet Union waged a titanic battle to the death against the Wehrmacht. It was essentially a necessary and inevitable wave of violence, as the American captain George Revelle Jr wrote to his wife as he prepared to land in Sicily: “We small men must resolve these catastrophes by destroying each other, to bring the world back to reason”.

Of all the major figures of the war, Kesselring remains for Italians if not the most hated, then at least one of the most hateful. Having opposed any chance of a surrender to the very end, he turned himself in to the Americans near Salzburg on the 6th May 1945. Tried in Mestre in 1947 for war crimes by a British court, he was sentenced to death. However, under pressure from General Alexander and Churchill, who believed that killing the leaders of a defeated enemy was not useful, his sentence was commuted first to life in prison and then to 21 years. In 1952 he was permanently released after a tumour appeared to worsen, but as soon as he was freed he returned to his home country, where he became a supporter of Bavarian Neo-nazi organisations, as well as a leader in the German Veteran Association, ‘Verband Deutscher Soldaten”. At that time he declared he had no regrets about his actions in Italy and even added that the Italians should erect a statue in his honour for the role he played in protecting cities of art like Rome and Florence.

Pietro Calamandrei, a former partisan and later a Social Democrat member of parliament, as well as a member of the Constituent Assembly, replied to those words at the end of 1952, with the composition “Lapide ad ignominia”, sculpted in marble and first delivered to Cuneo town hall and later to several other Italian municipalities:

“Comrade Kesselring

you will have

the monument you desire from us Italians

but we shall be the ones to decide

what stone we build it from.

not with the sooty pebbles

of the lifeless towns razed by your brutality

not with the earth of our cemeteries

where our young companions

rest in peace

not with the immaculate snow of the mountains

which for two winters defied you

not with the springtime of those valleys

that saw you flee.

Only with the silence of the victims

of a torture that was harder than any boulder

only with the rock of that pact

sworn by free men

who voluntarily gathered

in dignity, not in hatred

determined to redeem the world

of its shame and terror.

If you wish one day to return by these roads

to our lands, you will find us

dead and alive, with the same fortitude

a people serried around a monument

which now and forever

is called

Resistance”

Kesselring died in 1960, not of a tumour but of a heart attack, without ever repudiating his loyalty to Hitler.

The road home

My grandpa must have managed to reach Altopascio towards the end of July 1945, almost three years after he left Ginetta to depart for Corsica. I remember him telling me how difficult it was to move around Italy at that time. The rail and road networks had mostly been destroyed in the war, and there was no functional public transport that could cover such long distances. Not to mention that private transport was practically non-existent

The only alternative, then, was to negotiate a lift in one of the many military convoys that were still criss-crossing the peninsula, resigned to an uncomfortable journey of an unknown duration. To reach my grandma’s town, he had to spent whole nights lying on the dusty flatbeds of army trucks that groaned and bumped over the half-destroyed roads of central Italy. Sometimes he was lucky enough to come across a convoy going exactly in the right direction, covering a long distance in one stretch. Other times he was forced to change trucks several times just to cover a few kilometres or wait for hours before finding his next ride. Luckily, the war had accustomed him to eating whatever he could find and sleeping anywhere, his legs tucked up to his chest and the jacket of his uniform pulled up to his shoulders as a blanket.

When he finally came into sight of Altopascio, so impatient he was unable to stand still, he realized that he was dirty and suddenly felt embarrassed. He caught sight of himself in the broken windowpane of an abandoned house and realised he needed to freshen up at the very least.

He stopped to smoke a cigarette and forced himself to cast his mind back to the time he had spent there before leaving for Corsica. Running through the pictures in his mind, he managed to reconstruct the village streets and find one of the nearby ponds. When he reached it on that warm summer morning, the clear water was rippling, little frothy peaks catching the sunlight.

He decided in a second, unable to resist. He threw his cigarette on the ground, dropped his pack on the grass, took off his boots as he ran, and feeling relieved by a freedom that he hadn’t felt since he was a teenager, threw himself into the water fully clothed. The cool water hit him like a slap and for a second it took his breath away. He felt the dust of the previous days run off his skin and the muscles of his forehead relax for the first time in as long as he could remember.

Floating there, completely still, he lay looking at the sky for some time, feeling as if he had been given permission to come back to life. Emerging from the water, he removed his shirt and trousers and hung them on the branch of a tree to dry, before lying on the grass and falling into a peaceful, dreamless sleep, rocked by the warmth of the sun.

When he awoke, it was late afternoon and he felt like a new man, as if he had never faced hardship. His clothes were still a little damp, but dry enough to wear, especially in that summer heat.

He set off toward Ginetta’s house, hoping to find it still standing, given that around a third of the village had been destroyed during the war. The rubble and the empty spaces he saw on his way, where buildings used to be, told the story. Altopascio, just like the other places he had travelled through, seemed to be at the epicentre of a kind of organised chaos, in which the destruction wrought by the conflict had stopped, but whatever was to replace it had not yet arrived.

Putting one foot in front of another, his mind began to fill with doubt. Maybe he wouldn’t recognise Ginetta. Maybe he wouldn’t know what to say to her, how to feel. Maybe she no longer wanted him, after all that time and all that violence. He nervously lit a cigarette and when he realised that the hand holding it was shaking, he started laughing – could it be that he was more afraid now than before one of the many battles he had experienced during the war? But the thought of Ginetta had been one of the few things he could hold onto during the darkest hours, and he prayed that she hadn’t changed her mind.

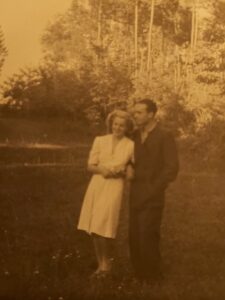

He finally saw her from afar, moving around in front of her house with her sister, both luckily unscathed by the war. Rather than any physical feature, he recognised her by her movements. A dull thud resounded in his chest, as if his heart had missed a beat, and he stood stock still, finally sure that he had found her.

He stood watching her, almost forgetting to breathe. The person he had imagined for so many years was finally in front of him, and seeing his fantasy made reality gave him a sensation of vertigo.

Finally, Ginetta slowed down, feeling that she was being watched. While she arranged her hair, distractedly, she began to look around her, looking for that inquiring gaze she felt on her, until she saw the outline of my grandpa, standing further along the pavement. She came to a sudden stop, her arm hanging strangely in mid-air. When her eyes finally focused on him, her hand flew up to cover her mouth.

Anyone seeing them at that moment would find them in suspended animation, their immobile bodies surrounded only by the chirping of the summer cicadas. At last, when my grandpa felt his shoulders begin to shake with a desire to cry, it was Ginetta that found the courage to go towards him. She took a few hesitant steps forward and then began to run, until her momentum ended in his arms.

They embraced with the force of a collision, plunging their faces into each other’s shoulders. Their fingers grasped the other’s back as if their lives depended on it, then they began to rock slowly back and forth, only able to murmur each other’s names.

After such a long time that neither knew how long it had lasted, my grandpa was the first to move his face to speak. They looked into each other’s eyes, while he stroked her hair. “I came back” he said, smiling.

“I prayed for you every day just like I promised, remember?” she asked, as a tear slipped down her cheek.

“Yes, I remember” he nodded. A few moments passed, then, trying to keep his voice steady, he asked her “Will you still recognise me after everything that’s happened? Do you think it’s possible?” He needed to know.

“I already know you, Adolfo. I know who you are” she replied, taking his face in her hands.

As he heard those words, my grandpa looked for some sign of uncertainty in her eyes, while her mind whirled with doubts. Perhaps she was only saying the first thing that came to her mind. Maybe she was stalling. Maybe she just wanted to see how he would react. But as he looked from one eye to another, he realised he saw not a glimmer of calculation.

He looked at her while she waited for him to react, her lips parted in anticipation. He closed his eyes and decided to insist: “But so much time has passed, Ginetta. How will we find our way back to each other?”

“We have our whole lives for that” she said, stroking him and drawing him back into her arms.

This time my grandpa gave in and nodded in silence, feeling her body rush into his arms. A moan escaped his lips: “I don’t think I would have made it without you” he said. And it was true, and it would continue to be true.

The relationship that kept them together for the next 63 years, until my grandpa’s death in 2008, was full of a visceral sentiment and courageous devotion, but was not lacking in scars. My grandpa, like many other men of that era, had physically survived the war, but had had his spirit irrevocably crushed. For the rest of his life, he forced my grandma to perform acrobatics to accommodate his schizophrenic love, lifting her up to the heights of generosity then plunging her into the depths of a nightmare, into his disgust with life and repressed anger, in an endless, inexplicable cycle.

But at that moment they knew little of what their love story would become, how they would live, and they cared little.

My grandpa stayed in Altopascio for the rest of the summer, oblivious to the passing of time and of the world going on around him. All that mattered to him was to stay there with Ginetta, enjoying the miracle of finally being able to see her every day. As the autumn arrived, with its cold wind, he was torn away from that haven of happiness, away from the world. Crossing the Apennines in winter would be impossible, and so the time had finally come for him to go home.

When he crossed the threshold of his family home in Ariano nel Polesine, he was swept up in his family’s love and his parents tears, but also in the pain of discovering that his sister Raffaella had died of pneumonia during his absence, and that his brother Enzo would not return home for another year, as he was still a British prisoner of war. It felt impossible for him to reconcile those two opposing feelings. So as not to be overwhelmed by it he began to plan his future with Ginetta, starting from his first trip to Altopascio in spring, and took comfort in the company of his dog, Argo.

I remember my grandpa telling me on several occasions about how Argo had welcomed him home after over three years of separation. When he saw him approaching the house, he began barking as if at a stranger, but fell suddenly silent when he heard him call his name. He sat still, one paw still raised, his ears pricked and his brow furrowed, his head cocked with a confused expression. “Argo, it’s me!” my grandpa said again. The dog approached shyly, sniffing first his leg, then his hand, unable to believe what was happening. When he finally realised that it was indeed my grandpa, he first began to run and jump back and forth, not knowing how best to celebrate, then began to cry inconsolably. My grandpa lifted him up and carried him into the house, paying him almost more attention than he did his parents, overcome with happiness. From that day forth, Argo followed him everywhere, to an almost obsessive degree, terrified of the possibility that he could lose him again, even sleeping at the foot of his bed to watch over him every night he was at home. In fact he often slept on the floor with him, as in the first few months my grandpa found it hard to get used to sleeping on a mattress, which seemed too soft for him after so many nights at war, curled up in a hole.

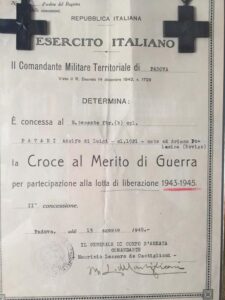

It took time, in the semi-destruction of postwar Italy, for my grandpa to organise his future with Ginetta. After several adventurous trips across the Apennines, one warm summer evening he finally decided to ask for her hand in marriage, which she accepted, closing her eyes and throwing her arms around his neck. A few weeks later, in August 1949, my grandpa was honoured with the War Merit Cross, awarded to every Italian soldier who had participated in the war of liberation. Those were happy days, full of promise and hopes for the future.

They were eventually married on 10th April 1950, after which they went on their honeymoon to Naples and the surrounding area, looking for places to enjoy their first dip in the sea of the season. When they returned home to begin their life as a married couple, my grandma packed her things, said goodbye to her family in Altopascio and joined my grandpa in Ariano nel Polesine, where at first they lived with his parents.

Over the years, they found their feet. My grandpa never went back to university and made no attempt to stay in the army. I think he had had enough, although he considered himself a bersagliere for the rest of his life, and never forgot to pay his annual fees to UNUCI, the Italian National Officer Veterans’ Union. In the end, he took up a modest post in a bank, and held on tightly to it until he retired. My grandma, on the other hand, found work as a primary school teacher and spent most of the 1950s teaching children to speak Italian, at a time when most still only knew their local dialect.

When they managed to move into their own house, they did not spend long there alone: they quickly started a family. The first of their two daughters was born in 1951 and was named Raffaella, after my grandpa’s lost sister. My mother, Silva, was born shortly afterwards, in 1952.

For their family holidays, which never varied over the years, my grandpa decided to buy a small apartment in Porto Recanati, in the Marche region, where I spent several summers with him, jumping in the sea, kicking a ball around the condominium’s courtyard and scattering my toys over every corner of the living room. I didn’t realise it at the time, but the choice of location was deliberate. The Musone river, where my grandpa had fought one of his most arduous battles, flows into the Adriatic Sea just five kilometres to the north and can be reached by an easy walk up the beach. Filottrano and Santa Maria Nuova, where he had seen so many of his companions fall, were not much further, about a half an hour’s drive inland. The Polish military cemetery, where those who died at the battle of Ancona lay and is one of the largest in Italy, is right next to Porto Recanati, in the nearby town of Loreto.

Over the years, my grandpa told no one about this, perhaps he would even have been incapable of explaining it. For his whole life he was unable to abandon his battlefields, caught in an exhausting balance between the days that lay ahead of him and the abyss of his past.

What remains

Having gone back over my grandpa’s life to the best of my abilities, spending the last few months trying to understand it as much as I could, I now write these final lines with a heavy heart, with the sense that I am saying goodbye to him again. Over the years, the hole he left in my life has stopped being a searing flame and turned into a deep hidden well, like a trapdoor that I must always be careful to avoid. A place I have to tiptoe around. As I write, I am turning his bersagliere hat over in my hands, which I received after he died and have jealously guarded since, and wondering what I have left of him after this journey.

My grandpa was, without a doubt, very different from the man that I have become. He spent his life in a constant state of overpowering love and fearless rage, with nothing in between. In his actions and his feelings, he never knew moderation, perhaps he never sought it. I remember disappointing him one day when I refused to go with him on our usual walk, as I was busy playing a game of make believe with other children in the courtyard of our building. “Oh, to hell with you!” he hissed, before turning on his heels and disappearing off down the street, leaving us speechless and in an embarrassed silence. Yet, in spite of a few occasions like that one, I always saw his eyes light up when he saw me, he spent long hours with me without hesitation and he gave his love generously through warm hugs.

When I compare myself to him, I consider myself more malleable, better able to accept compromises in life, even though I sometimes see in myself a glimmer of that lively, sometimes unpredictable flame that animated him. In spite of these seemingly irreconcilable differences, some of his features have come to the surface in my personality, making me the person I am today.

Firstly, my grandpa showed me how important it is not to be afraid of fear. Life will constantly present us with circumstances over which we have no control, but it never takes from us the ability to decide how to deal with them, as difficult as that may be.

When I first moved to Brussels I went through a fairly dark period, during which I often felt homesick, without a clear place in the world, far from my closest relations and suddenly alone, after the relationship that had brought me to that city ended, taking with it its stores of optimism and naïveté. I remember feeling suddenly overcome by events and, to my surprise, I began to feel a suffocating terror winding around my chest and throat, pulling me down into a dimension in which simple, everyday gestures, like walking around and talking to people, became progressively more difficult. Having spent some time trying to decipher the phenomenon, I realised to my dismay that I was suffering from panic attacks. I had always considered myself to be optimistic and carefree, and I couldn’t understand how that sort of thing could happen to someone like me.

Discovering that I could be fragile quickly swept away my self-confidence, and I descended into a dark hole where it was difficult to see a way out. Within a few weeks, I had begun to dread the mornings, when I had to force myself out of the house, go to work and behave in a more or less professional manner for the next few hours, when all I wanted to do was stay in bed asleep, or cry at my loneliness.

As the months passed, I realised that this was not a sustainable way of living. But I didn’t know which path to take, and I worried that I would not be able to save myself. One day, out of the blue, my grandpa called me. I didn’t have the courage to confess to any of my difficulties during that phone call, but hearing his voice reassured me. I stopped to think about the hardships that he had experienced in his life, and I thought that if he had had the courage to face his enemy head on, then so could I. With fear, of course, but with the dignity of someone doing their best, whatever the end result. For the first time, I had understood that there was no shame in feeling afraid, but that going through life with the aim of avoiding it would be a missed opportunity and an irreparable shame. From that day onwards, things began to improve for me.

My grandpa’s traumatic experience also showed me that I should not put too much store in the myth of strength, so often brandished as part of a stereotypical virility, the propaganda of those who have been lucky enough never to have had to face true violence and the terror it brings. Listening to his soldier stories and sensing the years of suffering that lay behind them, I gradually realised that war does nothing to toughen men up, it merely tears them apart, piece by piece, even if their body survives. And that nothing can prepare the human spirit for that sort of experience. Training, which my grandpa even imparted to new recruits at the end of his time in the military, can sharpen reflexes and condition muscle memory, but it cannot protect the spirit from the ravages it will face. Anything you could come up with in that respect would only be an illusion of control, manufactured and sold to make something indigestible appear attractive.

I remember him telling me several times about how he would get in his car and drive at top speed along country lanes before going home after work, on the worst days when he could not control his nightmares. He was trying to shake them off once and for all, his fingers gripping the steering wheel tightly, screaming in the privacy of his car, letting out all his bitterness and frustration. But it was an attempt doomed to failure, leaving him feeling emptier than before.

What I do miss, when I think about my grandpa, probably because it is a dimension that I lack in the breakneck speed of modern life, is the simplicity with which he lived out his days. His existence was always a paradigm of identical rituals, which he experienced with neither joy nor pain, just an acceptance that appeared to be the distillation of a higher understanding of life, in which both the importance and the transitory nature of human existence was clear.

Sometimes I pass by well-dressed, well-groomed men, either on the street or in the corridors of office buildings, who, with their determined gait and their carefully knotted ties seem to be doing everything possible to emanate confidence and impress everyone. But I just have to look at them for a few seconds to sense their fragility, their terror at the possibility of not being liked. My grandpa was the opposite of all that: a solid, spiky monolith, unable to pretend, in constant collision with life. One of those rare people who have the gift of showing you, with just a look or the touch of their hand, that there is no need to worry, everything will turn out fine.

My grandma, who had to put up with so much because of him, must have loved that about him. Because meeting him, you got the feeling that despite everything, he was made of love in its purest state, girded with trust.

The same trust I remember seeing in his eyes when, one summer morning, he had asked me if I wanted to go fly his new kite on the banks of the Po river. The kite was red and stuck out of the boot of the car, which he opened as I approached. At the grand old age of fourteen, it didn’t seem like a good idea. With an embarrassed smile I told him that I didn’t feel like it. Or that I didn’t have time. “Maybe another time, grandpa”, I added a moment later, to console him. But as I was saying it, he looked at me with sad eyes, as if he had already realised that it would never happen again.

I wish I could go back, hug him, and tell him I would love to.