I picture my grandpa sitting on the ship that is taking him to Corsica. It’s a cold November morning, clouds darken the sky and the sea is a grey and choppy desert. Several soldiers move around him. Each of them tries to fight fear in a different way: some clean their weapons, others smoke while gazing into the horizon, their hair beaten by the wind. Someone is playing cards in a corner, others are praying or writing letters. Nobody knows what to expect from the imminent landing. Will they be forced to fight or will they be able to reach their positions without firing?

My grandfather should be nervous like the others. He’s an officer and he feels the stares of his men on him, but his mind is somewhere else. The training in Pula, the promise to serve Italy, the conviction of being on the verge of something great: everything feels distant, as if it happened to someone else. Since a few days he is trapped in a dark room closing up on him, the rumble of the moving walls sounding like a sinister foreboding.

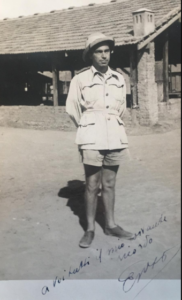

Upon completion of the officers’ school, he had left on leave. On the way back home he passed by Trieste. In those days, future felt like a bet to be accepted. The uniform made him feel confident and older than his age. Moving with a sense of purpose that was new to him, he met a Giulietta, a young girl from a rich family, who looked at him as if he was the only thing in the world and left her scent on his clothes.

A new experience for him. He had spent years in Ariano nel Polesine feeling almost invisible and doomed to a never changing existence. But now that he was a bersagliere and was about to leave Italy he had a look of invincibility in his eyes. Which is why he found rather easy to say goodbye to Giulietta and start chasing his destiny again, making light of her feelings. The noise of his quick and loud footsteps on the pavement, as she walked away from her in the evening, made him feel like a romantic hero. The idea that he had completely misunderstood the rules of the game had not yet crossed his mind.

He had been assigned to the XXXIII battalion of cyclist bersaglieri, based in Tuscany. He had therefore followed his unit up to the rally point, where preparations for the deployment had began. The nerve-racking wait was broken by the occasional drill or exhibition for the public, which flocked to the acrobatic shows of the bersaglieri on their motorbikes.

He met the girl who would become my grandmother during those summer days of 1942 in Altopascio, a village in the Province of Lucca. Her name was Gina, although she preferred to be called Ginetta, and she was a smiling lady with long hair, who used to smoke even though she was a woman. A habit that she would keep up for the rest of her life: every day, after lunch, she would open her kitchen window and smoke a cigarette in silence, watching her colorful geraniums on the balcony.

Her energy conquered him and he found himself writing songs for her and singing serenades under her window, accompanied by a harmonica he had hastily learnt to play. I remember when he was talking about it when I was a kid, on the way to school or during an afternoon walk: his eyes would look up to the sky and stare at a world that does not exist anymore.

He couldn’t quite explain what had happened to his determination or the desire to chase his destiny. Suddenly, they had become a passing and pointless thought. What he knew for sure was that he felt recognised for the first time in his life. And that his entire existence began and ended between her young and delicate hands.

Time passed like in a dream and when the month of November arrived reality crashed on them. The Allies were kicking the Axis armies out of North Africa and Hitler had decided to occupy the whole of France, fearing more landings on his southern flank. The Italians were tasked with the occupation of Corsica and the southeast of France.

The pace of events suddenly accelerated. The XXXIII bersaglieri battalion was assigned to Corsica and the landing had to take place as soon as possible. Mussolini was anxious to complete the mission and please Hitler.

The order to leave reached my grandpa before he could find the words to say goodbye. Something tried to find a way up his throat, but then got stuck there and the only thought he was able to formulate was that everything was always changing too fast. It wasn’t fair. We struggle to grasp happiness and then it slips away like sand through our fingers.

“I will pray for you every day”, Ginetta told him. “Come back to me alive”. He nodded in silence and hugged her before following his unit, feeling unable to breath in the stiff uniform, his legs as heavy as lead. They would see each other only two years later. Two grim years, as long as a lifetime.

Upon reaching the harbour in Livorno, my grandpa started writing his first letters to his family and Ginetta, trying to find words of affection and encouragement for everybody. But his attempts were cut short by an unexpected visit.

Somehow Giulietta had managed to find him. Challenging all social conventions, she had slipped out of her home and crossed half Italy to meet him in person before he left. She must have traveled holding on to a thin thread of hope and imagining their meeting an infinite number of times.

She found him just in time, a few hours before he boarded the ship. But when he saw her my grandfather looked only surprised. That look was enough for her to understand that it had all been in vain.

“It meant so much to me”, she told him throwing her arms around his neck, her eyes looking like a splintered cut on her face. My grandpa hugged her for a long time, breathing silently between her sobs. He then sat on the side of the road and watched her leaving, a silhouette on the horizon carrying away all the joys and pains of a rejected love, which nobody would ever live. His bold decision of a few months earlier suddenly looked wildly different, leaving him with one less life to live and the feeling of having to build his happiness on a pyramid of pain. In Trieste he had thrown away his innocence without even knowing it.

He should have taken her home. Or stayed there with Ginetta and help her going through the war. Or gone back home to his family, after his brother Enzo left for the frontline (he was already in a British prison camp by then, but my grandpa would discover it only after the war). Instead, he was watching the sea crashing into the shore as he was gathering his gear, ready to set sail for a future that looked like a mistake. He felt tired, worn out. Getting old is not the passing of time, but the weight of goodbyes.

It was however too late and there was nothing he could do anymore. He picked up his backpack and dragged himself aboard the ship. When they finally left, he looked at the other soldiers who, like him, were watching the land disappearing in silence. For a moment, the whole ship felt like a bottle of nostalgia thrown by someone into the waves.

The Italians landed in Corsica on November the 11th in Bastia and on November the 12th in Ajaccio and Bonifacio. The operation was tasked to the VII Army Corp, led by General Mondino. Roughly 150 ships, including civilian ones, were deployed to ferry the soldiers: the landings involved almost 70.000 men, to allow the Italian forces to face any event.

The plans for the occupation of Corsica had actually been drawn long before the landings. A strategy for its Italianization, starting from a joint administration of the island, was developed already in November 1940. The fascist regime had made its ambitions clear since the moment of France’s defeat in June 1940: the CIAF (Italian Armistice Commission with France) openly stated that Corsica was an Italian irrevocable aspiration. And Hitler himself granted Mussolini the right to occupy the island during a meeting held in Munich on June the 18th, 1940.

When the Italians moved towards Corsica, the local French garrison was ordered by the Vichy regime not to resist. They would have not stood a chance anyway: the Italians largely outnumbered them. The landings, which were preceded by a preparatory meeting between Admiral Tur and the French authorities, were therefore peaceful. The French soldiers on the island left it less than a month later: on December the 8th they moved out signing La Marseillaise after having destroyed their weapons and classified papers.

The Italian headquarter was established by General Mondino at the Hotel de la Paix in Corte, a little town with a citadel nestled in the mountains at the centre of the island. The same village became the base of the 10° Raggruppamento Celere, composed of Alpini and Bersaglieri (both elite units of the Italian army). It was a sort of rapid intervention force, to be mobilised in case of need. The XXXIII battalion of cyclist bersaglieri, to which my grandpa was assigned, was part of such unit and was housed in Vizzavona, a tiny village roughly 40 kilometres south of Corte, at an elevation of 900 metres.

Days were particularly cold in those mountains during the winter of 1942 – 1943. The temperature could sometimes drop several degrees below freezing and cycling around could become a fight against hypothermia. I remember my grandpa telling me how he and his men would at times help each other to remove their fingers from the handles at the end of a ride. Freezing temperatures would make them stick to the bicycles’ metal and freeing them required them to be slowly warmed up and extended, one by one, paying close attention not to break them.

After General Mondino, Italian forces were led by General Carboni and then General Magli. All of them had to manage a growing hostility between Italians and French. Italian troops were indeed very visible on the island, with one soldier for every three inhabitants, which felt like a continuous provocation. Regardless of the Italian authorities’ attempt to give the operation a purely defensive posture, against possible Allies’ attacks, the French were bound to perceive the invading troops as an occupation force.

To control the population, the circulation of cars and boats was limited. A curfew was introduced shortly afterwards. Local inhabitants started expressing their frustration by wearing French cockades, especially in Bastia. Or by refusing to unload Italian ships.

In the attempt of avoiding any incident, Mussolini intervened personally and sent precise instructions to the Italian army: “limit contacts to the operational needs, friendly but reserved attitude vis-à-vis the population, irreproachable discipline of the troops”. Such orders were confirmed by Admiral Tur, who stressed how every soldier had to “be an example of discipline, correctness and generosity towards those suffering morally and physically”.

In the beginning of 1943 however, the situation started deteriorating.

On January the 23rd British troops marched into Tripoli and conquered Libya, only 3 months after the battle of El Alamein. On January the 24th, the Casablanca conference ended with the announcement that Axis powers were required to surrender unconditionally. And on February the 2nd the Soviet Union finally prevailed in the battle of Stalingrad, in which Germans, Italians, Rumanians and Hungarians lost almost one million men. The Nazi wave had reached the high-water mark and from that moment on the Wehrmacht would have never recovered its original offensive capacity.

The wind had changed and the news of continuous defeats had plunged the morale of Italian troops in Corsica to a new low. The men started feeling lost, abandoned by their country in a region that was waking up and becoming increasingly hostile. Many soldiers started hoping for a quick end of the war. And the registries of the military tribunal in Bastia started showing a rapid increase in the episodes of insubordination, threats to superiors, defeatism and even voluntary wounds, self-inflicted by soldiers to be sent back home.

Nevertheless, Italian soldiers found a way to console themselves. Having come to terms with a prolonged stay on the island, they began having more and more contacts with local girls. From some initial isolated episodes, such behaviour became a widespread phenomenon. To the point that French authorities openly complained and suggested that women had to be “scared” in order not to encourage that “wave of immorality”.

When it came to punishing women, the Front National, i.e. the resistance movement of the French communist party created in 1941 (and not the far-right party led by Le Pen founded in 1972), for once agreed with the Vichy authorities. Threatening flyers therefore started to appear in cities and villages. One of them read: “These young women have a vile behaviour. Where are the pride, the legendary dignity of the women of Corsica? They are consumed by the fire of vice, which pushes them in the arms of our enemy”. Another one stated: “The sluts dishonouring our village will soon have to account for their behaviour”.

Threats became actions. At the end of the occupation, women who got too close to Italian soldiers had to endure the humiliation of a public head-shaving. The first episodes of this type of retaliation, which eventually spread across France, took place in Corsica. A punishment that smells of jealousy and misogyny.

I do not know whether my granpda, during those long months, also met a local girl. What I know for sure is that he remained in touch with my grandmother, trying to prevent time from turning her memory into a pure idea, without a body. Letters certainly helped, but phone calls even more, to hear her voice and give new shape to his memories. The whole village of Altopascio had only one telephone at that time and every time he called her, Ginetta had to be found by her neighbours in order reach the receiver and answer.

Between April and May 1943 the situation got even worse.

The North African campaign had ended and the increasingly threatening presence of the Allied navy in the Tyrrhenian Sea made the trip between Italy and Corsica more and more dangerous. This exacerbated the already existing supply problems of the Italian army, forcing a large number of soldiers to raid local farms and fields to eat, as well as to use their grenades to fish.

The scarcity of food also contributed to the development of a flourishing black market, where both Italians and French could sell products that had either been stolen or otherwise removed from normal market channels. The price of olive oil therefore jumped from 35 francs per litre to 250, wine from 10 to 100, potatoes from 8 to 35, fresh cheese from 39 to 200 and chestnut flour from 26 to 80. Corsica was becoming dangerously similar to a castle under siege, to be starved to defeat.

Given the circumstances, relationships between Italians and French could only become increasingly tense. And the resistance indeed started to act.

In April graffiti, flyers and songs threatening the Italians started to circulate. “Tremble, oppressors”, said some of them. Others read “To arms brave people of Corsica: death, death to the enemy”. Or “Between them and us it’s a fight to the death until their unconditional surrender”. In May, the first anti-Italian march took place in Ajaccio after Louis Frediani, a member of the Front National, was killed by an Italian soldier for violating the curfew. The day after, local shops remained closed and 2.000 people accompanied the body, to be buried in Ghisonaccia, to the train station. The crowd screamed for revenge.

From that moment on, ambushes to patrols, or attacks to Italian depots or vehicles, became more frequent. Before the end of July 1943, 16 soldiers were killed and 7 wounded in Corsica, as opposed to the 5 killed and 15 wounded in the whole of south-eastern France, the other area occupied by the Italians. The main targets of the attacks were the black shirts and the carabinieri, who were particularly disliked by the locals for being openly fascists, the former, or in charge of dealing with political prisoners, the latter.

The Italian repression however did not wait around. The OVRA (Organisation for the Monitoring and Repression of Antifascism), created in 1927, had offices in both Bastia and in Ajaccio, in the Marbeuf and Battesti barracks, and had a heavy hand. Several people accused of being partisans, or of cooperating with them, where imprisoned, executed or killed during military operations targeting the resistance. In total, 110 prominent citizens were imprisoned in the Prunelli di Fiumorbo camp, which hosted up to 44 inmates, or sent to the Elba Island. And several suspects were tortured with impunity. At least one of them, Louis Leca, died in this way, screaming his agony in the dreadful solitude of a torture chamber.

One of the last, horrifying episodes of violent repression took place on August the 30th. Some bersaglieri were tasked to execute partisan Jean Nicoli by shooting him in the back. Before they could do it however, he challenged them by screaming “Cowards! You don’t dare to look me in the eye”. The bersaglieri, puzzled and perhaps ashamed, dropped their weapons. For a long moment, it seemed that Nicoli’s courage would prevent his sentence from being executed. But this would have been intolerable for the Italian command. General Magli therefore intervened personally and replaced the bersaglieri with a squad of carabinieri. When they arrived, they jumped on Nicoli with uncontrollable fury and clubbed him wildly. After having knocked him on the ground, someone sat on his back, grabbed him by the hair and cut off his head with a knife.

By then my grandpa was not worried anymore about having made a mistake: he was sure of it. He found no glory in his duties and the bombastic rhetoric of the officers’ school sounded like a big pile of lies. Since days he had a bitter taste in his mouth that he could not spit out. The locals hated them. The Italian army had been defeated on all fronts. And the occupation of Corsica was spiralling into a nauseating tangle of hunger, fear of ambushes, retaliations and senseless violence.

He thought of Ginetta and her smile. He thought of the girl from Trieste, who had put her life in his hands. Those hands who had rejected her and were now holding a gun. He could not recognise them anymore and looking at them just made him want to scream. What the hell was he doing there?

The only positive note in those feverish days was the rescue of the local Jewish community. My grandpa was very glad about it: he did not join the army to indulge a sadistic Nazi whim and torment innocent people for no reason.

As soon as the Italian occupation had been completed, the Nazis started asking for all the Jews in Corsica and south-eastern France to be rounded up and imprisoned. On December the 14th 1942, Italian authorities therefore created a dedicated body, led by OVRA, to manage the so-called Jewish question. It was however just window-dressing. A few days later, on December the 29th, General Trabucchi, 4th Army’s chief of staff in charge of the occupation of France and future partisan leader, declared that “the supreme command ordered to forbid (…) the imprisonment of Jewish people”. And on January the 14th 1943, the Italian Consul-general in France, following orders of the Foreign Affair Minister Galeazzo Ciano, indicated that Italian authorities would refuse to impose the indication of “Jew” on identity cards.

Many were the reasons explaining the choices of Italian authorities, all tangled up and probably all true at the same time. Firstly, regardless of the Italian racial laws of 1938, fascism was not profoundly rooted in anti-Semitism like Nazism. Secondly, the Italians wanted to show their independence from the Germans and mark their sovereignty over the French territory they had claimed. Furthermore, several prominent fascists had accumulated part of their wealth in the USA and were therefore unable to ignore the American diplomatic action in favour of Jewish communities, deployed also through the Vatican. Finally, decision-makers had probably understood that Nazism was eventually going to be defeated and that protecting Jews could have been used as a bargain chip during the inevitable peace talks with the Allies.

Clearly, the Italian approach was not welcomed by Nazi Germany. In February 1943, Himmler sent Foreign Affair Minister Ribbentrop to Rome, to complain directly with Mussolini. The Duce initially tried to resist but then yielded, removing Galeazzo Ciano and appointing himself as the new Minister of Foreign Affairs. The operational management of the Ministry was however assigned to the former Vice-secretary of the Fascist Party Giuseppe Bastianini, who was appointed Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs. One of his first actions was to inform the Germans, on March the 20th, that the Italian authorities had appointed Guido Lospinoso, a trusted fascist, to the role of Inspector General of the racial police in order to settle the thorny Jewish question.

Luckily, the Nazis did not realise who they were dealing with and decided to trust Lospinoso. He turned out to be a cunning bluffer and a master in playing both sides.

Firstly, he postponed his departure and moved to Nice only at the beginning of May. Once there, he immediately arranged a meeting with Angelo Donati, an Italian Jew and a successful businessman, who had already manoeuvred to protect the Jews in occupied France. Lospinoso wrote in his papers that he had found him to be “a distinguished gentleman and full of good will”, who could act as a useful “trait d’union with the Jewish community”.

After that, he started working on his cover-up, with the patience of a spider. He minimised his contacts with both German and French authorities. He moved lists of Jews to arrest from one desk to another, until they were lost. He promised the Nazis to cooperate and did not keep his word. And when some arrests became inevitable, he made sure that the Jews were moved to pre-established locations on the Alps without resorting to violence.

The Germans, frustrated, looked for a way to break the deadlock and identified their ideal target in Donati, who was pictured as the representative of the Italian Jews’ financial interests, so powerful as to be able to jeopardise the action of the fascist regime. The Gestapo therefore planned to kidnap him, but eventually had to cancel the action, for fear of diplomatic consequences with Italy.

In Corsica, a small group of 57 Jews aged between 18 and 60 was rounded up in the northern part of the island and moved to the village of Asco, in the school building. The camp was opened on May the 15th, 1943. However, the situation never became dangerous: the Jews were not allowed to leave the village but were free to cook, have visitors, interact with the locals and receive pocket money for the their daily expenses. And most importantly they were not deported.

In his memories, Lospinoso always denied that Mussolini backed him, even just tacitly. According to him, Jews were therefore rescued only thanks to the initiative of the Italian army, authorities and private citizens involved in the events of those dramatic days.

After the war, Bastianini was cleared of all charges for the role he played in the fascist regime. Donati became an Italian diplomat and received, in 2004, the posthumous Gold Medal for Civil Valor. Lospinoso, after having been accused of antisemitism, was found innocent thanks to the testimonies collected and was eventually appointed chief of the police in Udine. However, Italian authorities never granted him any award: his actions remain, to this day, nearly unknown. According to various estimates, roughly 25.000 Jews living in Corsica and south-eastern France were saved from extermination camps thanks to the intervention of these and other Italians.

The summer of 1943 was a dark period for my grandpa, almost hopeless. However, everything was about to change. He couldn’t know it yet, but he would soon receive his baptism of fire alongside those who, at that moment, would have gladly stared at him down the barrel of a gun. His opportunity of redemption was, by now, just around the corner.